- Home

- Cherie Priest

Those Who Went Remain There Still

Those Who Went Remain There Still Read online

Those Who Went Remain There Still

Copyright © 2008 by Cherie Priest.

All rights reserved.

Dust jacket and interior illustrations

Copyright © 2008 by Mark Geyer.

All rights reserved.

Interior design Copyright © 2008

by Desert Isle Design, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Electronic Edition

ISBN

978-1-59606-372-3

Subterranean Press

PO Box 190106

Burton, MI 48519

www.subterraneanpress.com

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

This one’s for

all my friends and family

in the Bluegrass State

No gypsy slut nor doxy,

shall win my Mad Tom from me

I’ll weep all night, the stars I’ll fight,

the fray shall well become me.

— from “Mad Maudlin’s Search

for Her Tom of Bedlam”

Author unknown

Acknowledgements

Even the cheesiest little monster stories don’t happen without help, and this one took a bundle. I’ll start by thanking my darling husband Aric, who brings home the bacon and the health insurance so that I can stay home and write my cheesy little monster stories. Thanks also goes to Dear Mr. Schafer, who takes the most marvelous chances on newbies like me; to my agent Jennifer Jackson, who must be one of the busiest people alive (but she always has time for emailed questions and nervous phone calls); and to my sister, who does not yet know that she’s going to get stuck helping me with the final pass proof edits for this manuscript. I’m not above bribing her if need be, and she’s usually game to help give me a read, so I’m pretty confident that I won’t feel silly about including this note once the book is actually in print.

Likewise, I extend my fondest thanks to Mike Owen and Laura Middleton, who took one for the team by investigating Rock City for me, in order to track down the source of this book’s title. (It’s kind of a long story.) Thanks also to Ron Nagy from the Lily Dale Assembly, who tried to help me prove that John Coy had lived in that town, once upon a time.

And strangely enough, a great deal of additional thanks goes to my mother, Sharon Priest. My mom is a generally helpful soul, so it’s not strange that she would lend a hand, really—except that she hates scary stories and has never read a single one of mine. The odds are exceedingly good that she’ll never read this one, either, but this did not prevent her from rummaging about through storage and digging up old genealogy records at my behest. She helped me confirm some of the historical specifics even though she knew exactly what I was going to do with them, and she’ll probably be mortified by the final product. I greatly appreciate that, despite her reservations, she’s been such a good sport about the whole thing.

So yes, in case you read this book but skip the accompanying chapbook, it’s worth noting that this short novel is inspired by an old family tale which—sadly enough—features no actual monsters in its original incarnation. I assure you that this retelling rectifies reality’s troubling oversight in this matter.

I

In the Beginning: Reflections upon the Wilderness Road, Daniel Boone, 1775

We’d been cutting since March, and we were almost done.

Back at the start, there were thirty-six of us. By fall, we were down to twenty-two men.

***

You could blame a couple of our losses on the Shawnee. Them and the Chickamaugas, they didn’t agree to any Transylvania treaty, and they didn’t think we belonged there. But we only lost two men to the natives and the rest of us kept on cutting. Then one man got taken by a bear, back in June. It was a big old momma, with a couple of round, fat babies. She got him good, but he ought to have known better.

Three more we lost just to being sick, or hurt, or working too hard. One of them, an axe-head came flying off a handle and notched his shoulder, and the wound didn’t look too bad except how it wouldn’t heal right. It was a real trouble, an accident like that, but it wasn’t the kind of dying that scared men off a task.

It was the rest of them, the other eight. They were the ones we were scared about.

But we couldn’t do anything except keep our eyes open and our axes swinging. We were almost to the Kentucky River, and it was stupid of me, maybe, but I thought if we could just get to the river, we’d be all right.

***

We’d brought that Road from Virginia to the middle of Kentucky, almost 200 miles. We blazed that Road up through the Cumberland Gap just like I said we would, and I promised we’d clean it up until we got into the thick of the new territory.

Well, we sure got into the thick of something.

I just kept on thinking about the river, and I kept thinking about the flying thing, and the way it swayed and waddled up there between the treetops. It was heavy—too heavy to fly, almost. It was all the creature could do to hop and flap between the branches.

I kept thinking, If we can just get ourselves across that river, it’ll be wide enough that once we cross, the thing won’t be able to follow us. Maybe I was just saying that because it gave us a goal, and it made the men feel like there was a safe place ahead. I hoped I wasn’t lying to them.

But I’d seen a lot of strange things out there, out where nobody walks but the Indians in their deerskin moccasins. I’d seen cats the size of ponies, almost; and I’d seen bears with chests like barrels, and heads like a moon’s eclipse.

For all my time out in the trees, and for all the years I spent watching, hunting, and taming the wild spots between the little cities…I’d never seen anything like that.

***

To tell it true, for a long time we could hardly see it at all.

***

The creature mostly came at night, and at first, it mostly came for the food we’d caught and were keeping. We figured it must be coyotes. Wolves will catch and kill their own food, but a coyote isn’t above stealing it. They’re lazy things, and sneaky and fast. But we weren’t hurting for food, and we found it aggravating, not frightening.

It was strange, though, about the food. Coyotes will take your store, but they won’t foul what they leave. They might come back and take the rest later, but they don’t shit on it out of spite.

***

When the trouble began in earnest, it was still late summer, or the very earliest fall. Mostly it was plenty hot, and we ought to have found lots of game. Up until fall we shot long-legged, fawn-gray deer and heavy little turkeys. We found plenty of nuts and bushels of berries.

But it got harder and harder to hunt down meat. All the game went wandering off, getting scarce. We had to travel farther and farther away from the Road in order to find anything at all; it was like the whole forest knew there was danger, and it wasn’t just a few dozen men clearing a path.

***

We were armed, all of us.

We each had a sharp axe, at least—and some of us had guns and arrows, too. We weren’t homesteaders, waiting helpless. We came ready for trouble, and ready to hand out trouble.

But we had no idea—none at all—and it got worse every day. We only got hungrier, and more nervous as the weeks ticked by and we worked hard, sunup to sundown, and there were shadows covering the stars. Terrible smells came pouring through t

he camp like the stench of death itself, and all night we heard the sound of wings bigger than wagon wheels, flapping up above like the snap and unsnap of an umbrella.

***

The first man went missing all of a sudden, and after that the creature took somebody almost every other night. Towards the end it slowed down some, going two or even three nights without stealing anyone. We must’ve been getting harder to grab. That thing pared us down to the fastest, and the hardest to hold.

Those of us who remained were going to give it one hell of a fight, if that’s what it wanted.

But the first one, he didn’t know. None of us knew, and we weren’t even sure what happened. All we knew was that it was dark and he was screaming, and along with his screaming we heard something else. It was a louder noise than a man could’ve made. It came from a bigger chest, a raspy honking, something like a goose—and something like the shriek of a big cat. If you’ve ever heard one of those cats, you know what I mean. They sound like a woman, almost, like she’s screaming for help. It’s a noise that’ll make your blood run cool, and make you sweat at the same time. Imagine that cry, if you can, and imagine it with a croak.

I’m not saying what I mean too well.

***

Anyway, he was taken and we were suddenly short another warm body, and we didn’t like that too much. But we kept cutting. Deep down we knew it wasn’t a cat, and it wasn’t a wolf, either. Any fool knows the sound of a wolf. Even people who’ve never heard it before, they’ll recognize the howl and run away from it, if they’ve got any sense.

We talked about how it might be a bear, but bears just roar and that’s a sound we all knew. So it wasn’t a bear, either.

It was about as big as one, though, and it moved above us, and not beside us. We’d been learning, by trial and error, by glimpse and fast-moving wink between the trees.

Whatever it was, it was flesh and blood, and feathers too. We found the feathers sometimes in the morning—huge brown things tipped with gray and a rubbed copper color. Someone said that it must be an owl, and if we hadn’t been so tired, hungry, and mad, we would’ve laughed at him.

I’d seen owls the size of dogs, and I’d seen turkeys even bigger than that. But none of them leaves feathers as long as a small canoe, or as wide as a fat man’s leg. No, our visitor was bigger than I was. It was bigger even than Little Heaster, who we called “little” because it was funny. That boy wasn’t eighteen yet, but he was a head and a half bigger than the rest of us.

The creature was stronger than we were too, and it must’ve seen real good in the dark. Maybe light hurt its eyes. Anyway, it didn’t like the fire. That’s why we built it up so big at night. We thought maybe if camp was bright enough and hot enough, we’d keep the thing away.

***

See, it’s never been the axes that separate us from the beasts. It’s not steel, and not tools, and not roads. It’s the fire, that’s all. Everything under creation—everything on four legs and everything that swims or flies or crawls—every living thing except for a man will shy far from a flame.

***

And night kept falling fast. It fell faster every dusk, or we were losing more of our daylight gathering and hacking up fuel to burn.

Come night, the birds quit calling and the squirrels, porcupines, and lizards all quit their scurrying. Nothing moved beneath the leaves on the floor between the tree trunks. Nothing crawled across the boulders pushed down the hills by the gullywashing rains.

The sky went orange, then lilac. Then it went gray and took on a touch of blue.

Those nights, I would’ve been happy to hear the howling chatter of a pack of wolves. Those nights it would’ve warmed my heart to hear that lady-fierce scream that says a mountain lion is hungry nearby.

We made a fire so bright we couldn’t see the moon. We had our steel and we had arms so used to swinging, we could snap down oaks in our sleep. Between us, we could keep away a cat or a whole crowd of dogs.

We all huddled close to the edges of the fire—so close that we almost got burned, and we were so hot we could barely stand it.

***

Not far away, not nearly far enough away, we caught a loud series of pops.

It was a strange sound, and when it came we heard the high-up branches crack and fall. The pops were harsh and hollow, and they climbed through the sky like wings lifted up by the beating of a drum.

Over and over again, it was the fast, low snap you hear when a strong-armed woman throws open a wet blanket.

II

Ames, Iowa–1899

I was eighteen when I left Leitchfield, and I had my reasons. I had them by the bushel.

Same as everyone else I was born there, at home. And same as everyone else I was brought up confused, and hateful in a way. It could be that we’re just a fractious lot, as old Heaster Jr. used to say. Maybe we were all born ready to squabble and we wouldn’t have liked one another anyhow, but most people blamed the feuding on the war.

You had to blame it on something, if you weren’t going to blame it on yourself.

The way things split up was like this: Heaster Jr. was the great granddaddy of us all—either by blood or by marriage. And by blood or by marriage, most of his offspring (leastways, most of us who stayed in the valley) had wound up wearing one of two last names, Coy or Mander.

When the war broke out and Kentucky was asked to choose sides, we went both ways on both sides of the church rows, but it mostly broke down by family lines. The Manders sent eleven sons, brothers, and cousins up to the Union. They got seven of them back. The Coys sent thirteen sons, brothers, and cousins to the Confederacy. They got back four.

One of the ones who came back was my daddy, Everett Coy. He married Mona Manny in 1870 and I happened along nine months and three days after. They named me Meshack, and I didn’t know until I was a grown man how they’d spelled it wrong. Momma said she’d heard it in church and thought it sounded nice. Daddy never said anything about it, ‘cause he died when he got kicked in the head by a horse, and I was just ten. Neither one of them, Momma or Daddy, could read or write hardly, and I don’t hold that against them and I’m not saying they were stupid. I’m just saying there was no one there to teach them, so they didn’t know.

That’s how it worked there, in the bluegrass hills. You learned how to live close to the land because you weren’t close to much else.

There weren’t many people except those you were related to, and probably fighting with. There weren’t many towns closer than several days away, and once you got there you’d need money to do anything.

Well, we didn’t have any money. So we made just about everything for ourselves. Oh, sometimes we traded for something—mostly we swapped homebrewed alcohol for staples like cloth, nails, and seed. But mostly, if we couldn’t make it ourselves we went without it.

***

That went for books, same as the rest of it. We only had one school, and it wasn’t open half the year, and sometimes it wasn’t open that much—depending on the teacher. Our preacher could read, and if you gave him the right kind of moonshine he might teach you a few letters, but he was a cold old fellow who shouted at us about love. He beat us with words of kindness. He kicked us with commands that we should be gentle and patient.

Most of us didn’t like him much. But my momma would go, every Sunday. She would sit there with my little sister, Winnter, and they would rest themselves on those wood-slat pews so hard you could’ve cracked nuts on them. I don’t know what they learned there, that they liked it enough to go back every week. By the time I was old enough to listen good, I was old enough to work—so I worked, and I didn’t get any other education until I left.

***

I would’ve left when Daddy died, if I’d been able. Momma told me then how I was the man of the house, me being oldest. She explained how I had new responsibilities, with her getting old and a baby sister to love after. Momma wasn’t twenty-five when that happened.

She was younger then than

I was when I went back.

I’d like to tell you how that gives me some perspective, and how I’m more understanding about why she did the things she did, but that’d be a lie. I understood well enough then that she was crazy, and I could see in Winnter—in the way her eyes went wild sometimes, and the way she would laugh and cry or hug or hit for no real reason—I could see something mad was in the family. And I spent half my life praying, “Not me, too. Whatever it was, don’t let me have caught it too.”

***

For a long time, I thought there might be hope for Winnter. I thought if nothing else, maybe she’d marry good. She was real pretty, with hair that copper-brown color you see on birds, and those eyes that were blue and speckled gold. She was too thin, but we were all too thin from not eating right, or enough. She couldn’t read or write, but most of us couldn’t either, so it weren’t no strike against her.

But she could make a rhubarb pie that would make Jesus himself crawl down from the cross to lick his fingers. And she could sew real fine—she could mend up anything, and if there was cloth enough, she could make up her own dresses and they were as good as anything you’d see in a city catalog.

And like I said, she was awful pretty.

It didn’t matter, though. The older she got the more she behaved like Momma. I tried to guide her some, because she was my responsibility and because I loved her. I wanted her to understand that just because she lived with Momma, and just because she looked like her, she didn’t have to be her. She didn’t have to turn into the lonely, crazy old spinster who hates the whole world—Mander, Coy, and everybody else, too. I tried to tell her there were other laces and other families, other spots where she could go and get more for herself.

I told her, “There’s a whole world outside of Leitchfield. There’s a whole bunch of other states, outside of Kentucky. There’s a whole bunch of other people you could grow up and marry, and not a one of them has to be from anyplace you’ve ever heard of.”

Maplecroft

Maplecroft Chapelwood

Chapelwood Fathom

Fathom Hellbent

Hellbent Jacaranda

Jacaranda Four and Twenty Blackbirds

Four and Twenty Blackbirds Dreadnought

Dreadnought Dreadful Skin

Dreadful Skin Bloodshot

Bloodshot Tanglefoot

Tanglefoot Clementine

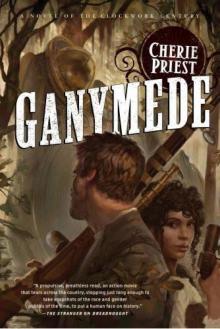

Clementine Ganymede

Ganymede The Inexplicables

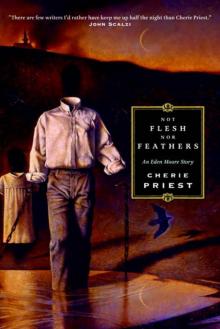

The Inexplicables Not Flesh Nor Feathers

Not Flesh Nor Feathers Wings to the Kingdom

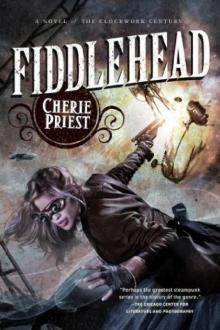

Wings to the Kingdom Fiddlehead

Fiddlehead Tanglefoot: A Story of the Clockwork Century

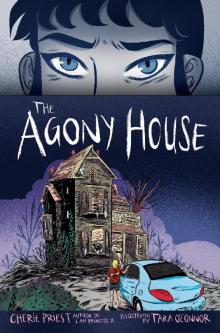

Tanglefoot: A Story of the Clockwork Century The Agony House

The Agony House Ganymede (Clockwork Century)

Ganymede (Clockwork Century) The Inexplicables (Clockwork Century)

The Inexplicables (Clockwork Century) Clementine tcc-2

Clementine tcc-2 Grants Pass

Grants Pass Dreadnought tcc-3

Dreadnought tcc-3 Ganymede tcc-4

Ganymede tcc-4