- Home

- Cherie Priest

Dreadful Skin Page 10

Dreadful Skin Read online

Page 10

Page 10

But I hadn't learned enough. I hadn't learned how to kill him; I'd only learned that I must kill him, because there would be no stopping or redeeming him.

God might have disagreed with me—but as of that moment where I was staggering in the unoccupied cabin, trying to gain my balance and my bearing, He'd never told me so.

XII.

People were starting to come out of their cabins, wandering into the rain, wondering what that godawful noise had been. They were milling about, walking along that edge of panic—when the unknown is something yet uncertain, but bound to be terrible. I imagined they were right, but I didn't believe it would do any of us any good to embrace a frightened frenzy.

Two of the young men from supper were out on the deck—I told them about the mud drums, and how they make such a horrific noise that unseasoned travelers often fear the boiler is about to explode.

I knew as well as the serving girl knew that it was a lie. It calmed them anyway. I've always been a good liar.

I told them to go back to their rooms and prepare for bed. We'd be stopped for the night, and they may as well rest. I told them that I would do likewise, but then I heard the screaming, and I knew that the bluff was up.

It wasn't that howling sound—no. It was a woman in terror, or fury.

Based only on suspicion, I thought it must have been the serving girl, Laura. There was a primitive brutality to the sound, it was something less civilized than I thought an educated Irish woman might produce. It was not a sound that would come from a small woman, anyway; and Laura was a tall girl. Furthermore, something told me she wasn't a nervous girl, prone to histrionics.

And she was screaming.

Only for a moment. It would be more accurate to say she emitted one great scream, and stopped. But it was a scream of decidedly imminent peril.

Several heads popped out of their respective cabins, but I ignored them—I don't know why. I might have called for help, though they might have thought to help me on their own, and I don't know why they didn't.

Out in the elements—buffeted by the cascades and stings of the uncooperative weather—I ran toward the place where the scream might have originated. On the way and on a whim, I ducked back into the dining area and rushed to the kitchen.

Laura had taken the biggest knife, but I did not intend to charge headlong into danger unattended. I found a large serving fork. It was the size of my forearm, with three giant fangs as long as fingers. It might have looked silly, but it was heavy in my hand and I thought it would suffice.

Back into the rain. I was shocked; it hit my face as hard as a slap. It all but blinded me. It confused me, but I heard fast footsteps off to my right—so I chased them.

"Laura! Sister Eileen!" I called out. Nothing answered, so I kept following the patter, though it'd grown faint between the raindrops. I was following their memory more than their echo.

I was down the hall from the captain's cabin, I thought. He might have been a tired old drunk, but he was the captain—he was the boat's authority—and I thought that this must be a good time to rouse him. Strange things were happening on the Mary Byrd, and they were surely worse than strange. They were sinister.

But it was then that I realized why Laura had been screaming.

I came upon the captain's cabin and was stunned into immobility. I stared into his cabin with my mouth agape, collecting the raindrops that streamed from my hair and down my chin.

His cabin had become a slaughterhouse.

The captain was sprawled, his chest and head on the floor—his feet and thighs on the divan. He was perfectly dead, without a doubt. No one lives while missing so much of his face and throat. Hardly any bit above his chest was recognizable, but for one bulging blue eye that pointed sightlessly at the ceiling.

His hands were torn and bruised too, and his wrists; he'd held them out to hold something else away. But what?

I thought of Laura with her knife, but I did not see her and I was not foolish enough to think she was responsible. No, it was only fear I felt for her, when I thought about her roaming the decks alone with her knife.

And where was she?

A crash might have answered me—or it might have told me nothing. At least it startled me away from the sight on the floor of the demolished cabin. At least it gave me something to look for and think about besides, "Where did the rest of him go?"

The crash was mighty, but brief. It sounded like a window breaking and taking part of a wall with it—it was decidedly different from the thunderclaps that coughed themselves into the sky every few minutes. The Mary Byrd shook a little—or maybe she just rolled with a river wave. The wind was moving her too.

The frantic patter of footsteps had been drowned by the rain, so I changed my approach and went toward the stern, toward the crash—or so I thought.

I skidded around the corner and found myself overlooking the big red paddlewheel. I caught myself on the railing's edge before I could topple down into it, and I thanked heaven and lucky stars both.

I turned around and saw where a window was gone, blasted inside the cabin as if something large and unwilling had been thrown through it. It pained me—I hesitated, and I cringed, but I looked inside anyway. I expected to see something as horrible as the captain's room, but there was nothing. Only the evidence of a struggle—shards of glass, toppled books, a chair with one leg smashed out from under it.

And blood.

I saw a little bit of blood. But it wasn't much. It was a small, splattered amount running thin with the added influx of rainwater; it suggested discomfort and inconvenience, not death. Whoever was hurt had left the scene.

"Laura?" I shouted again. "Sister Eileen?"

I tore myself away from the broken window and fought the wind-thrown rain again—I held out my arm, with my elbow pointed forward, trying to clear myself a path through the sheets of water. It hardly helped. I could hardly see.

And that's why I plowed right into him—the cook. He was a bigly muscled man like I was in my youth, and he was as black as a plum with brown eyes set in yellow. My head connected with his collarbone and I recoiled with apologies begging from my lips.

"I didn't see you there," I told him. "I—" I wiped my face on my sleeve and continued. "I wonder, did Laura find you?"

He didn't react, except to stand there and sway.

I felt warmth in my hair, dripping down my face. I wiped it again with my sleeve—and only then noticed something stained and streaked upon it. It wasn't mine, I didn't think.

"Cook?" Between the rain and the darkness I couldn't make out much detail in his visage. But he was wearing a gray night shirt and it was just light enough to spy the way he had both arms raised up to clutch his chest, and his throat. And his skin was so dark that I hadn't seen, until I looked for it, that all of his soaking came not from the rain.

I reached out a hand to him—though I don't know how I meant to help.

He reached a hand to me—though there wasn't anything I could do. I saw that, when he took the hand away. I saw white there, underneath his grasp. It was bone, and tendons, and the cords of his throat.

Before he could take my hand, he fell slowly sideways. I stepped forward to catch him or assist him—at least to lie him down on the deck, perhaps, and give him that passing measure of dignity. His weight bore him down though, harder than I could hold him up. He toppled past me. His hip cracked against the rail and broke it—the bone or the rail, I don't know, I only heard it—but over the side he went, and he splashed down into the Tennessee River. He bobbed a moment or two before sinking, or being washed away to a spot I couldn't see.

I stared down after him, gasping, panting, breathing in the rain and wishing for the sun—for God, for Eileen, or Laura, or anyone.

And above me, up on the hurricane deck and between the gonging beats of thunder, I heard the unmistakable sound of a struggle.

XIII.

The cook's room was empty when I finally got to it. His cabin looked all right, but the door was hanging open and water was blowing on in. I came inside and looked around, pushing the door shut behind me enough so I could shake the water off myself.

"Cook?" I called, but it was obvious he wasn't there, and I don't know why I bothered.

The room was tidy and didn't have much in it, like mine. He didn't own much, and what he had was stashed like his mama told him how to do it. The only thing undone was the bed—the covers were pushed aside and the sheets were unmade. It looked like he'd turned in for the night and maybe heard something. Maybe he got up, out from between the sheets, and maybe he opened that door.

Whatever happened after, he hadn't closed it and he was gone.

I opened the door again and went back into the wet. It didn't matter. I was soaked all the way down to my skin everywhere anyway. And if finding the captain had taught me anything, it was that hiding in a cabin wouldn't do me no good, and probably my knife wouldn't either.

Out on the deck I stepped on something that crunched and slipped. It was a lantern, or what was left of one—the glass kind filled with oil. The cook probably took it with him when he left the room to see what the noise was. And he'd dropped it, but he'd been lucky—or we'd been lucky. Either the rain or chance had kept it from bursting into flames along the deck and setting us all ablaze.

But there were my hints—an open cabin door, a broken lantern, and an unmade bed. No cook. And out in the cabin decks someone was surely going to find the captain soon.

And someone was shooting—once, twice, maybe a third time—the thunder got in the way of what I heard, but I heard the first two clearly enough. Someone was shooting, and that couldn't mean anything good.

I thought of the pilot's house, up on top of the boat, and I thought of the big whistle there. It was a whistle you could hear for miles, if you kicked the treadle wheel with all you were worth. You could sure hear it farther off than a gunshot, I'd bet.

Somewhere back towards the captain's cabin I heard a big commotion, but it sounded too close to have come from there.

Maplecroft

Maplecroft Chapelwood

Chapelwood Fathom

Fathom Hellbent

Hellbent Jacaranda

Jacaranda Four and Twenty Blackbirds

Four and Twenty Blackbirds Dreadnought

Dreadnought Dreadful Skin

Dreadful Skin Bloodshot

Bloodshot Tanglefoot

Tanglefoot Clementine

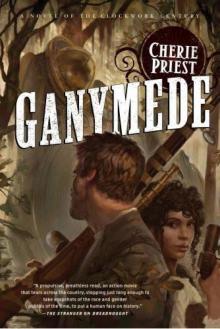

Clementine Ganymede

Ganymede The Inexplicables

The Inexplicables Not Flesh Nor Feathers

Not Flesh Nor Feathers Wings to the Kingdom

Wings to the Kingdom Fiddlehead

Fiddlehead Tanglefoot: A Story of the Clockwork Century

Tanglefoot: A Story of the Clockwork Century The Agony House

The Agony House Ganymede (Clockwork Century)

Ganymede (Clockwork Century) The Inexplicables (Clockwork Century)

The Inexplicables (Clockwork Century) Clementine tcc-2

Clementine tcc-2 Grants Pass

Grants Pass Dreadnought tcc-3

Dreadnought tcc-3 Ganymede tcc-4

Ganymede tcc-4