- Home

- Cherie Priest

The Inexplicables (Clockwork Century) Page 13

The Inexplicables (Clockwork Century) Read online

Page 13

“Right. Rumor has it he’s keen to get inside the wall and look around. And that’s not a rumor I like very much. The sharks are circling, Wreck. So if you hear of anybody from the outside getting any ambitions about coming inside, I want you to speak up. It’ll be best for you if you do—and best if you tell it to the Station before you say anything to those other guys.”

Rector’s nose felt like it was running. He wiped it with the back of his shirtsleeve, and tried not to notice the dump, yellowish stain that streaked the fabric. “Funny, you bringing that up. Harry did the same, when I stopped by his place the other day.”

“I’m not surprised. We’re worried, and we’re watching. One way or another, they’re coming for us. And it’s not like we don’t have enough problems down here, with the gas and all.”

“And all?” Rector asked, trying to sound innocent, and failing with great aplomb.

Bishop shook his head. “There’s talk about something bad walking the northern blocks. More than one something, we think; they’ve been spotted up on the walls, too. Not sure if they’re men, or animals, or what, but they’re big.”

“Do they … do they chase people? Kill ’em?” Rector gulped. “Eat ’em?”

Bishop lowered his voice to reply, enough that Rector almost thought that the chemist was playing with his head. “We’ve lost four guys in the last two weeks. Found nothing left of them but pieces, like they’d been yanked limb from limb.”

Rector’s mouth was too dry to swallow again. “Limb … from limb?”

“So keep an eye on yourself, if you’re going to be hanging around them Doornails. We don’t mind them keeping to themselves, but maybe they’re not alone. And maybe they’ve got ideas, and won’t keep to themselves forever. Don’t be a trusting fool about their company.”

“Jesus, Bishop. I can take care of myself.”

“That remains to be seen. However, you haven’t made a grab for the sap that’s not six inches from your hand, and you’re looking … I don’t know, clearer. You look more clear than last time I saw you. Maybe you’ll pull yourself together yet.”

“I do appreciate your confidence. So are you going to help me out, or do I have to find that crazy Chinese kid and get him to take me all the way back to where I came from? Because I sure as shit can’t find it on my own.” He left off what he thought about saying next, that he didn’t have the energy to make the trip anyway.

Bishop rose to his feet. He wasn’t a tall man, or a heavy one, either, and he wore a big brown leather apron over his clothes stained the same yellow as Rector’s sleeve, and pocked with burn marks. Bishop reached for a row of round knobs, and as he turned them one by one, a soft hiss of gas fussed out through the pipes. The cooking flames lowered, and the glass containers settled down to a simmer.

“All right, Wreck. If all you need’s a place to put your head, I can stick you someplace quiet.”

Rector laughed with relief. When he stood up again, he nearly collapsed, but caught himself. “Thanks, Bishop. Thanks a whole bunch, man. I want you to know I appreciate it.”

And as Bishop gathered up a satchel and a handful of tools, he said, “And I want you to know I expect you to keep an eye on those Doornails for us. You’re not their kind, kid. You’re ours. And you’d better remember it.”

Twelve

After spending the night in a clean, if sparsely fitted railroad car, Rector awoke to Houjin’s insistent knock on the door.

Once Rector was awake enough to get his boots on, he let Huey take him back to the Vaults, where he slept for almost another full day on the same bed in the sickroom where he’d first awakened. No one had given him anyplace else to sleep, so he went back to the spot he knew, and he took it.

He awoke to an empty room.

If anyone had come or gone since Houjin left him there, he had no way of knowing it, and he was alone now. But he remembered the way to the washroom, and he remembered the way to the kitchen. Since an empty bladder and a full stomach were his most pressing needs, he didn’t mind the privacy. He didn’t mind the peace and quiet, either, considering that both of the guys he knew down there were chatterboxes from the word go. But the longer he was by himself, the more he had time to think.

Thinking wasn’t his favorite thing to do, and it wasn’t his strong suit, though he didn’t consider himself a dummy by any means. No, mostly he didn’t want to think because he didn’t trust his thinking engine.

He knew he’d done bad things to his head, using all that sap over all those years. His whole life, it felt like. Well, not his whole life. The sap had a way of burning up old memories, as if it consumed them for fuel. He wanted some now, just short of desperately.

And here he’d been hoping it’d get easier as time distanced him from his last use of the stuff.

How long had it been? About a week, plenty of which was spent unconscious. Did unconscious time count, when it came to breaking a habit? A second thought came on the heels of that one: Could he find his way back to the Station unaided?

They’d have some there, obviously. He’d seen it right there, in Bishop’s workshop. Bishop hadn’t moved the packet, even after pointing out it was there and noting that Rector hadn’t made a dive for it. Maybe it’d be there still tomorrow, or whenever he could reach it next. For one awful flare of a moment, even the specter of Yaozu’s unhappy face couldn’t temper the awful need.

No. He couldn’t have any sap. He had a job to do, and Yaozu had no use for addicts.

Knowing this, remembering this, and clinging to this still didn’t take the edge off how badly he wanted the drug. But it steeled his resolve enough to keep him from setting off for King Street Station right that instant on a lark.

Barely.

Instead, he resolved his way down to the kitchen, without the cane this time. He was disappointed to learn that the cherry supply had not been replenished, but he was able to scavenge enough odds and ends, bits and pieces, and stray scraps of perfectly serviceable food from inside the cabinets and barrels to fill his stomach.

It was pleasant, this sense of being full. Over the years, he’d lost track of what it felt like. The sensation was quite different from his old way of managing his hunger, which was to load himself up on drugs until he simply forgot that he hadn’t eaten enough in a long time.

But even once he was content, he didn’t want to stop at “full.” A lifetime of paranoia about his next meal made him want to grab everything and hoard it, but he stopped himself from filling his mostly empty satchel with whatever he could carry from the kitchen. He’d left most of the bag’s contents under the sickroom bed since no one seemed inclined to take them away from him, except the pickles and he didn’t need any of the foodstuffs right at that moment. He’d kept the lighting supplies and added the mask he’d been using, plus extra filters and other small sundries—including a little pot of foul-smelling cream he’d found on the table beside his bed next to a note that read simply, in blocky print, “Fer your hands. And stop scratchin at them.”

Gloves still eluded him, but they were next on his list. He needed a pair if he planned to run around up top, and he had a mission—a real-live bona fide job, given to him by someone who nobody argued with.

The more he thought about it, the more he liked it.

He moved with the authority of the city’s “mayor.” So long as he stayed in his good graces, no harm would come to him. He mused on this pleasant fact while he chewed, eating so thoughtfully that he almost didn’t hear the odd thumping noise that came from down the hall. When it did penetrate his thoughts, he concluded that it moved with the rhythm of footsteps—and when the stepper appeared, Rector froze like a small wild animal.

All his smug, hypothetical confidence evaporated on contact with the man who stood in the kitchen doorway, because he nearly filled it. He wasn’t as tall as Captain Cly—and who was, really?—but he looked like a man Cly’s length who had been squashed down to merely average height. He had a wide, flat face and arms as t

hick as railroad ties. In his hand, he held a cane sturdy enough to support a moose.

“Hello,” Rector peeped.

The man said hello back, with only a faint note of a question. Then he said, “You’re Rector, aren’t you?”

“I am.”

“Been out cold for the last day or so, haven’t you?”

“I have.”

“Huh,” he said, and approached the same cabinets that Rector had so freshly raided. “I heard about your hair. Hard to miss a boy like you.”

“So I’m told.”

“I’m Jeremiah, but half the folks down here just call me Swakhammer,” he informed Rector, not looking at him. He was too busy rummaging, hunting for something in particular. Still facedown in the storage, he added, “The nurse who’s been looking after you—that’s my daughter.”

Rector said, “Ah. Yes. She seems to have done a bang-up job.”

“She always does. So, what about you?” Swakhammer turned around with a paper-wrapped piece of something smelly in his hands. Peeling the old newsprint aside, he revealed a slab of smoked salmon that Rector wished to God he’d seen first, because it’d be camped out in his stomach by now if he had.

“What about me?”

“Are you roaming around in the Vaults all by your lonesome?”

“For the moment,” Rector confirmed. “I’ve only been up a little while. I don’t guess you know where Huey or Zeke might be, do you?”

“Both of them are up at the fort, I think. Huey flies with the Naamah Darling more often than not, and Zeke is trying to learn something from the captain—or trying to keep from learning anything, I can’t tell which.” He bit off a hunk of fish, and held the rest by its wrapping. As he chewed, he leaned back against the counter and spoke around the mouthful. “You want me to take you up there? Or do you know the way?”

Somewhat relaxed by Swakhammer’s attitude, if not his appearance, Rector said, “That’d be fine, if you don’t mind showing me. I’ve only been there once, and I wasn’t half awake yet.”

“All right, then. Hey, that’s a real nice satchel you got there.”

Oh yes. Huey had said something about it being one of Swakhammer’s. “I understand it’s one of yours,” he said—might as well play it straight, for there was no arguing now. “I appreciate you letting me hang on to it. Or … Huey said you wouldn’t mind.”

“Yeah, I don’t care. Got a bunch of them. Scavenged them out of an old army post years ago. Can’t say enough for the Union’s craftsmanship; they sure do make good bags. I think those things would survive … well, shit. They survive in here, don’t they? That’s a recommendation for ’em. They ought to advertise it. They’d sell ’em by the pound. Come on, I’ll take you back to the fort.”

Rector hoped that the man with a cane would take an easier path than the nimble Houjin, and he was glad to see that Swakhammer did indeed skip the stairs when possible. “We’re going to go the easy way. I don’t feel like stomping over every hill and through every holler. Got myself tore up last year, and sometimes I think this leg will never heal all the way.”

“Sorry to hear that.”

“Wasn’t your fault. Anyhow, put on your mask, and I’ll put on mine. I say that to warn you: Mine is a real humdinger.”

As Rector extracted his own gear, he watched Swakhammer pull a huge contraption off a sling over his shoulder. It looked too big to be a mask, but wasn’t; and it didn’t look like a mask at first glance, but it was.

“Humdinger,” Rector echoed with a whistle. “Where’d you get that thing?”

Swakhammer shrugged himself into the mask. The contraption fell over his head, and its edges settled on his shoulders. With the adjustment of a few straps and buckles it was affixed firmly, if weirdly.

“How do I look?” he asked. Every word sounded like it came through a tin can on a string.

“Like…” Rector struggled for words. “Like a horse that someone put in a suit of armor. Sort of.”

Swakhammer laughed, which was also rendered into a metallic sound that came from far away.

“Good enough. I’ve heard ‘clockwork warthog’ more than once, but ‘horse’ is a first. This thing was made by Minnericht, rest his soul … or don’t, I don’t care. But I keep it around because I can breathe real good in it. Masks run small on a man with a neck like mine.”

Privately, Rector thought that Swakhammer had no neck at all. It was as if he’d been carved from a brick, all one set of lines.

“I wish we didn’t have to wear them down under here. Didn’t used to. But since the cave-ins, we’ve gotta do it just to be safe.”

As they walked together, Rector thought this might be a good time to put his salesman skills to work. Or were they detecting skills? He liked the idea of being a detective better. He wasn’t talking people into buying anything; he was asking for information, not money. And in his limited experience, people parted with information a whole lot easier.

“Mr. Swakhammer,” he broached. “How long do you think it’ll be until the underground’s safe for breathing again?”

“That partly depends on Yaozu and his men at the Station, and the Chinamen, too. I think we probably need them more than they need us, ’cause they got plenty of men and we don’t. But these shoring rigs”—he pointed at the ceiling, which sagged ominously despite a set of planks that had been braced to hold it—“they’re not worth a damn. Once those engineering fellows finish up in Chinatown—they’re fixing their own blocks first, you know how it goes—they’ll bring the equipment up here and we can buttress our ceiling all proper-like.”

“Equipment?”

“Mostly leftovers from when the Station was built. They’ve got steam-powered machines they’ve refitted to haul, lift, and brace. We couldn’t do it with sweat and elbow grease alone—not unless we had about a thousand more of us than we’ve got. The Chinamen got digging machines over there, too. I don’t understand it myself, but Huey was telling me that sometimes you gotta dig holes in order to fix holes. I just leave that sort of thinking to him.”

“He’s a smart one, that Huey.”

“I didn’t used to care for that kid, or any of the Chinatown folks. But after I got blown up last year, Doctor Wong put me back together. Now my daughter works with him, and she says he’s all right and I have to keep an open mind. So there you go. You can tell her when you see her that I’m keeping an open mind.”

Rector nodded and kept the easy pace set by the big man with the cane. They ducked beneath low-hanging boards and clumps of bricks that had once been arched, and stepped on hollow walkways made of planks where such walkways were available.

And before he could decide what to ask next, Swakhammer said almost softly—or so Rector thought, given the buzzing quality of his words—“I hope we get it fixed up soon. I want it to be safe. For Mercy, if not for me. I mean, if she’s going to be damn fool enough to stay here.”

Sensing an opening, Rector pounced. “Yaozu told me he’s working on it.”

Swakhammer drew up short, then continued. “That’s right, Zeke said he’d called for you, and you’d gone out to the Station. How’d that go, anyhow?”

“Not bad. Mostly he wanted to make sure I wasn’t going to make no trouble.”

“You got a reputation for doing that?”

“No sir, I don’t.

“Got a reputation for fibbing out loud, I bet.”

“Aw, that’s not called for,” Rector protested weakly. “I’m a salesman, is all.”

“Same thing.”

“No sir, it isn’t.”

Swakhammer made a sound that could’ve been a laugh, and pointed the way up a corridor. “Not much farther.”

Rector was glad he’d let it go. “Good. I’m still a little on the feeble side, myself. I don’t suppose there’s an easier way up topside…?” he broached.

“Sure, if you want to get eaten by rotters.” But something about the way he said it was uncertain.

“Ain’t seen h

ardly any rotters,” Rector pressed. “I heard there was scads of ’em here, but Yaozu said there aren’t as many as there used to be.”

Swakhammer stopped, and although nothing of his face could be seen inside that amazing mask, his posture suggested that he was thinking about this. “There’s truth to that. At first I figured it was my imagination, but now I’m not so sure. It’s the order of the day, though—things disappearing. People disappearing.”

“I don’t understand…?”

“Mercy will tell you all about it. It’s not a coincidence, not anymore.” Swakhammer shook his head, as if this was a subject he’d rather not consider. So he said, “It’s not just the rotters. The population up there”—he gestured with his hands as though he was feeling around for the right thing to say—“It’s changing. The rotters are disappearing, but there are more birds, and the rats are coming back.”

Rector shuddered. “Rotter rats and birds?”

“No, not exactly. The air’s different for them, I don’t know why. It makes them sick, real sick—like mad dogs. But it doesn’t kill them. It doesn’t leave them roaming brainless and dead.” He shifted his shoulders and resumed course, waving for Rector to come along. “I don’t know how they’re getting in.”

“What if they’re getting inside the same way the rotters are getting outside?”

“Who said rotters were getting outside?” Swakhammer asked quickly. Even through the mask, reading between the mechanical lines of his speech, Rector thought he sounded entirely too innocent.

“Nobody. I just thought, if there were fewer rotters, they must be going someplace. And like you said, there’s no place for them to go. Except out.”

“You’re a real thinker, ain’t you?”

“Not usually. I’m just new here. Still learning the ropes.”

“You listen: If you ever think there’s a breach in the wall, you speak up, all right? We can’t have these things getting out. And it ain’t particularly good to have other things getting in.”

“Other things?” The shadow of a long-armed monster flicked through his memory, and he fought the urge to hug himself. “What other things?”

Maplecroft

Maplecroft Chapelwood

Chapelwood Fathom

Fathom Hellbent

Hellbent Jacaranda

Jacaranda Four and Twenty Blackbirds

Four and Twenty Blackbirds Dreadnought

Dreadnought Dreadful Skin

Dreadful Skin Bloodshot

Bloodshot Tanglefoot

Tanglefoot Clementine

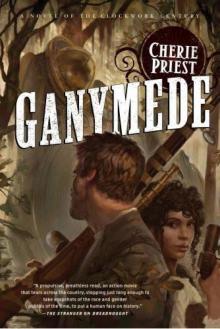

Clementine Ganymede

Ganymede The Inexplicables

The Inexplicables Not Flesh Nor Feathers

Not Flesh Nor Feathers Wings to the Kingdom

Wings to the Kingdom Fiddlehead

Fiddlehead Tanglefoot: A Story of the Clockwork Century

Tanglefoot: A Story of the Clockwork Century The Agony House

The Agony House Ganymede (Clockwork Century)

Ganymede (Clockwork Century) The Inexplicables (Clockwork Century)

The Inexplicables (Clockwork Century) Clementine tcc-2

Clementine tcc-2 Grants Pass

Grants Pass Dreadnought tcc-3

Dreadnought tcc-3 Ganymede tcc-4

Ganymede tcc-4