- Home

- Cherie Priest

Clementine tcc-2 Page 2

Clementine tcc-2 Read online

Page 2

They were so close now, Hainey could see the horse’s mouths chomping against the bits, and the strain of their haunches as they surged to move the wagons. He could see the hasty streaks of a too-rushed paint job on the side of his former craft, covering up the silver painted words that said Free Crow.

It was a ridiculous thing that Brink had done, sillier than sticking a false nose or mustache on the president of the United States. No air pirate at any port on any coast would have mistaken the repurposed war dirigible for any other vessel.

“Sir-” Simeon said, but he had nothing to follow it.

“Hang on,” Hainey said to his first mate and engineer. His feet jammed against the pedals to turn the ship, and it turned, slowly, shifting midair and sliding sideways almost underneath the Free Crow-until the front deployment hooks were aimed at the only place where there wasn’t any armor. Then he ordered, “Fire hooks!”

Simeon didn’t ask questions. He jerked the console lever and a loud pop announced the hooks had been projected from their moorings. The hissing fuss of hydraulics filled the cabin but it wasn’t half so important as the scraping thunk of the hooks hitting home.

“Cut thrusters, and retract!” Hainey shouted. “Retract, retract, retract!”

Simeon flipped the winding crank out of its holding seam and turned it as fast as he could, his elbow pumping like a train’s pistons until the nameless ship’s shifting position became more than a tip-it was a tilt, and a firm, decided lean. “Got it sir,” he said, puffing hard and then gasping with surprise when his elbow was forced to stop. “That’s as far as we can bring them back.”

“It’s enough,” Hainey swore, and it must have been, because the nameless ship was swaying all but sideways, drawn up underneath the Free Crow.

The Free Crow’s left thruster fired up against the nameless ship’s hull, down at the cargo bay where it scorched a streak of peeling paint and straining, warping metal. The engine chewed hard at the unimportant bits of the latched-on ship, but the ships were bound together like bumblebees mating and now, they could only move together.

Hainey’s thrusters had been cut at the collision, and inertia pushed the ships together in a ballroom sway that made a wide arch away from the temporary docks. Locked as they were, the ships made half of a massive, terrible spiral until the right thrusters on the Free Crow blasted out a full-power explosion-jerking both the vessels and tightening the gyre until the ships were simply spinning together, a thousand feet above the plains.

Within the nameless ship all men grasped everything solid, and Simeon even closed his eyes. He said, “Sir, I don’t know if I can-”

“You can take it,” Hainey told him. “Hang on, and hang in there. We’re going down.”

“Down?” Lamar asked, as if saying it aloud might change the answer.

“Down,” the captain affirmed. “But it’s a carousel of the damned we’ve got here; it’s…hang on. Jesus, just hang on.”

The landscape rotated in the windshield, pirouetting first to the brown grasslands below, and then to the brilliant blue and white sky, and then back to the horizon line, which leaped alarmingly, and then again, to the earth that was coming up so fast.

In glimpses, in those awful seconds between spinning and falling and crashing, Hainey saw a tiny corner of the Free Crow’s front panel and he could spy, through the glass, a tumbling terror on the deck of his beloved ship-and it pleased him. He tried to count, in order to make something productive of the frantic moments; he saw the red-haired captain, and a long-haired man who might’ve been an Indian. He saw a helmeted fellow, he thought; and for a moment he believed he saw a second long-haired man, but he might’ve been wrong.

The ground lurched up and the nameless ship lurched down, until there was nothing else to be seen out through the windshield and the end was most certainly nigh. Hainey covered his head with his hands and Simeon propped his feet up on the console, locking his legs and ducking his own head too.

And a tearing, ripping, snapping noise was accompanied by a yanking sensation.

“What was that?” Lamar shrieked.

No one knew, so no one answered-not until the second loud breaking launched the nameless ship loose from the Free Crow, and flung it into the sky.

“The cables!” Hainey hollered, calling attention to the problem even as it was far too late to do anything about it. “Thrusters, air brakes, all of it, on, now!” He slapped at the buttons to ignite the thrusters again and tried to orient himself enough to steer, but the ship was light and it was flying as if clipped from a centrifuge and they were no longer falling, but destined to fall and to skid.

The thrusters burped to life and Hainey aimed them at the ground, wherever he could spot it.

Simeon said, “We have to get up again. We have to get some height under us.”

“I’m working on it!” Hainey told him.

But the thrusters weren’t enough to fight the gravity and torque of the broken hook cables, and the downward spiral cut itself off with an ear-splitting, skimming drag along the prairie that jolted all three men down to their very bones. The ship tore against the ground, and the men’s bodies were battered in their seats; the dust and earth scraped into the engines, into the burned cargo bay, and into the bridge; and in another minute more, the unnamed ship ground itself to a stop while the so-called Clementine staggered across the sky towards Kansas City.

2. MARIA ISABELLA BOYD

Maria Isabella Boyd had never had a job like this one, though she told herself that detective work wasn’t really so different from spying. It was all the same sort of thing, wasn’t it? Passing information from the people who concealed it to the people who desired it. This was courier work of a dangerous kind, but she was frankly desperate. She was nearly forty years old and two husbands down-one dead, one divorced-and the Confederacy had rejected her offers of further service. Twenty years of helpful secret-stealing had made her a notorious woman, entirely too well known for further espionage work; and the subsequent acting career hadn’t done anything to lower her profile. For that matter, one of her husbands had come from the Union navy-and even her old friend General Jackson confessed that her loyalties appeared questionable.

The accusation stung. The exhaustion of her widow’s inheritance and the infidelity of her second spouse stung also. The quiet withdrawal of her military pension was further indignity, and the career prospects for a woman her age were slim and mostly unsavory.

So when the Pinkerton National Detective Agency made her an offer, Maria was grateful-even if she was none too thrilled about relocating to the shores of Lake Michigan.

But money in Chicago was better than poverty in Virginia. She accepted the position, moved what few belongings she cared enough to keep into a small apartment above a laundry, and reported to Allan Pinkerton in his wood-and-glass office on the east side of the city.

The elderly Scotsman gave her a glance when she cleared her throat to announce that she stood in his doorway. Her eyes were level with the painted glass window that announced his name and position, and her hand lingered on the knob until he told her, “Come in, Mrs.…well, I’m not sure what it is, these days. How many men’s names have you worn?”

“Only three,” she said. “Including my father’s-and that’s the one I was born with. If it throws you that much, call me Miss Boyd and don’t worry with the rest. Just don’t call me ‘Belle.’”

“Only three, and no one calls you Belle. I can live with that, unless you’re here to sniff about for a new set of rings.”

“You offering?” she asked.

“Not on your life. I’d sooner sleep in a sack full of snakes.”

“Then I’ll cross you off my list.”

He set his pen aside and templed his fingers under the fluffy, angular muttonchops that framed his jawline like a slipped halo. His eyebrows were magnificent in their wildness and volume, and his cheeks were deeply cut with laugh lines, which struck Maria as strange. She honestly couldn’t imagi

ne that the sharp, dour man behind the desk had ever cracked a smile.

“Mr. Pinkerton,” she began.

“Yes, that’s what you’ll call me. I’m glad we’ve gotten that squared away, and there are a few other things that need to be out in the open, don’t you think?”

“I do think that maybe-”

“Good. I’m glad we agree. And I think we can likewise agree that circumstances must be strange indeed to find us under the same roof, neither of us spying on anyone. This having been said, as one former secret-slinger to another, it’s a bit of a curiosity and even, I’d go so far as to admit, a little bit of an honor to find you standing here.”

“Likewise, I’m sure.” And although he hadn’t yet invited her to take a seat, Maria took one anyway and adjusted her skirts to make the sitting easier. The size of her dress made the move a noisy operation but she didn’t apologize and he didn’t stop talking.

“There are two things I want to establish before we talk about your job here, and those two things are as follows: One, I’m not spying for the boys in blue; and two, you’re not spying for the boys in gray. I’m confident of both these things, but I suspect you’re not, and I thought you might be wondering, so I figured I’d say it and have done with it. I’m out of that racket, and out of it for good. And you’re out of that racket, God knows, or you wouldn’t be here sitting in front of me. If there was any job on earth that the Rebs would throw your way, you’d have taken it sooner than coming here; I’d bet my life on it.”

She didn’t want to say it, but she did. “You’re right. One hundred percent. And since you prefer to be so frank about it, yes, I’m here because I have absolutely no place else to go. If that pleases you, then kindly keep it to yourself. If this is some ridiculous show-some theatrical bit of masculine pride that’s titillated at the thought of seeing me brought low, then you can stick it up your ass and I’ll find my way back to Virginia now, if that’s all right with you.”

His rolling brogue didn’t miss a beat. He said, “I’m not sticking anything up my ass, and you’re not going anywhere. I wouldn’t have asked you here if I didn’t think you were worth something to me, and I’m not going to show you off like you’re a doll in a case. You’re here to work, and that’s what you’ll do. I just want us both to be clear on the mechanics of this. In this office, we do a lot of work for the Union whether we like it or not-and mostly, we don’t.”

“Why’s that?” she asked, and she asked it fast, in order to fit it in.

“Well maybe you haven’t heard or maybe you didn’t know I didn’t like it, but the Union threw us off a job. We were watching Lincoln, and he was fine. Nobody killed him, even though a fellow or two did try it. But this goddamned stupid Secret Service claimed priority and there you go, now he’s injured for good and out of office. Grant wouldn’t have us back, so I don’t mind telling you that I don’t mind telling them that they can go to hell. But they can pay like hell, too, and sometimes we work for them, mostly labor disputes, draft riots, and the like. And I need to know that you can keep your own sensibilities out of it.”

“You’re questioning my ability to perform as a professional.”

“Damn right I’m questioning it. And answer me straight, will this be a problem?”

Maria glared, and crossed her legs with a loud rustle of fabric. “I’m not happy about it, I think that’s obvious enough. I don’t want to be here, not really; and I don’t want to work for the Union, not at all. But I gave the best years of my life to the Confederacy, and then I got tossed aside when they thought maybe I wasn’t true enough to keep them happy.”

He said, “You’re speaking of your Union lad. I bet old Stonewall and precious Mr. Davis sent you a damned fine set of wedding china.”

She ignored the jab and said, “My husband’s name was Samuel and he was a good man, regardless of the coat he wore. Good men on both sides have their reasons for fighting.”

“Yes, and bad men too, but I’ll take your word for his character. Look, Miss Boyd-I know how good you are. I know what you’re capable of, and I know what a pain in the neck you’ve been to the boys in blue, and it might be worth your peace of mind to know that I’ve taken a bit of guff for bringing you here.”

“Guff?” she asked with a lifted eyebrow.

He repeated, “Guff. The unfriendly kind, but this is my operation and I run it how I like, and I bring anyone I damn well please into my company. But I’m telling you about the guff so you’re ready to receive it, because I promise, you’re going to. Many of the men here, they aren’t the sort who are prone to any deep allegiance to any team, side, country, or company; they work for money, and the rest can rot.”

“They’re mercenaries.”

He agreed, “Yes. Of a kind. And most of those fellows don’t care about who you are or whatever you did before you came here. They understand I take in strays, because strays are the ones you can count on, more often than not.”

She said, “At least if you feed them.”

He pointed a finger at her and said, “Yes. I’m glad we understand one another. And you’ll understand most of my men just fine. But I’ve got a handful who think I’m a fool, though they don’t dare say it to my face. They think you’re here to stab me in the back, or sabotage the agency, or wreak some weird havoc of your own. That’s partly because they’re suspicious bastards, and partly because they don’t know how you’ve come to my employ. I haven’t told them about your circumstances, for they’re nobody’s business but your own. You can share all you like or keep it to yourself.”

“I appreciate that,” she said with honesty. “You’ve been more than fair; I’m almost tempted to say you’ve been downright kind.”

“And that’s not something I hear every day. Don’t go spreading it around, or you’ll ruin my reputation. And don’t assume I’m doing this to be nice, either. It won’t do me any good to have a team full of people who don’t respect each other, and maybe they won’t respect you if they think you’re here due to hard times. They’ll give you a wider berth if they think I campaigned to bring you here, and that might put you on something like equal footing-or at least, footing as equal as you’re likely to find in a room full of men.” He didn’t exactly make a point of dropping his eyes to her chest, but his gaze flickered in such a fashion that she gathered the point he’d avoided making.

She didn’t stiffen or bristle. She reclined a few inches, which changed the angle of her cleavage in a way she’d found to be effective without overt. Then she said, “I know what you’re getting at, and I don’t like it. For whatever it’s worth, I’ve never been the whore they called me, but the Lord gives all of us gifts, and mine has never been my face.”

He replied with a flat voice that tried to tell her she was barking up an indifferent tree. “It’s not what’s beneath your boning, either. It’s what’s between your ears.”

“You’re a gentleman to say so.”

“I’d be an idiot if I didn’t point it out,” he argued. “You’re a competent woman, Miss Boyd, and I value competence beneath few other things. I trust you to sort out any issues with your fellow agents in whatever manner you see fit, and I trust you to make a good faith effort to keep disruption to a minimum.”

“You can absolutely trust me on that point,” she confirmed.

“Excellent. Then I suppose it’s time to talk about your first assignment.”

She almost said, “Already?” but she did not. Instead she said, “So soon?” which wasn’t much different, and she wished she’d thought of something else.

“You’d prefer to take a few days, get the lay of the office, and get to know your coworkers?” he asked.

“It’d be nice.”

He snapped, “So would a two-inch steak, but the soldiers get all the beef these days and I’ll survive without it. Likewise, you’ll survive without any settling-in time. We’ve got you a desk you won’t need, and a company account with money that you will. I hope you haven’t unpacked ye

t, because we’re sending you on the road.”

“All right,” she said. “That’s fine. And yes, I’m still packed. I can be out the door in an hour, if it comes down to it. Just tell me what you need, and where you want me to go.”

He said, “That’s the spirit, and here’s the story: We’ve got a problem with two dirigibles coming east over the Rockies. The first one is a transport ship called the Clementine. As I understand it, or as I choose to believe it, Clementine moves food and goods back and forth along the lines; but she was getting some work done over on the west coast. Now she’s headed home, and the government doesn’t want her busted up.”

Maria asked, “And the second ship?”

“The second ship is trying to bust her up. I don’t know why, and if the Union knows, nobody there is willing to talk about it.” He picked up a scrap of paper with a telegram message pecked upon it. “I’m not going to lie to you. Something smells funny about this.”

She frowned. “So…I don’t understand. This second ship is following the first? Harassing it? Trying to shoot it down?”

“Something like that. Whatever it’s doing, the officer who’s expecting his Clementine back in service doesn’t want to see it chased, harassed, harried, or otherwise inconvenienced on its return trip. And part of the Union’s displeasure with the situation comes from a rumor. Let me ask you a question, Miss Boyd. Are you familiar with the fugitive and criminal Croggon Beauregard Hainey?”

She knew the name, but she didn’t know much about its owner and she said so. “A runaway Negro, isn’t that right? One of the Macon Madmen? Or am I thinking of the wrong fellow?”

Maplecroft

Maplecroft Chapelwood

Chapelwood Fathom

Fathom Hellbent

Hellbent Jacaranda

Jacaranda Four and Twenty Blackbirds

Four and Twenty Blackbirds Dreadnought

Dreadnought Dreadful Skin

Dreadful Skin Bloodshot

Bloodshot Tanglefoot

Tanglefoot Clementine

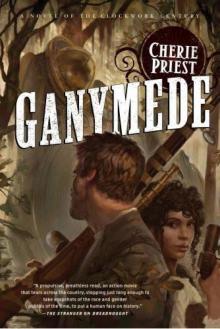

Clementine Ganymede

Ganymede The Inexplicables

The Inexplicables Not Flesh Nor Feathers

Not Flesh Nor Feathers Wings to the Kingdom

Wings to the Kingdom Fiddlehead

Fiddlehead Tanglefoot: A Story of the Clockwork Century

Tanglefoot: A Story of the Clockwork Century The Agony House

The Agony House Ganymede (Clockwork Century)

Ganymede (Clockwork Century) The Inexplicables (Clockwork Century)

The Inexplicables (Clockwork Century) Clementine tcc-2

Clementine tcc-2 Grants Pass

Grants Pass Dreadnought tcc-3

Dreadnought tcc-3 Ganymede tcc-4

Ganymede tcc-4