- Home

- Cherie Priest

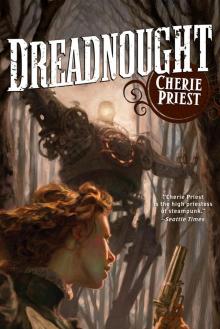

Dreadnought tcc-3 Page 3

Dreadnought tcc-3 Read online

Page 3

Someone authoritative cried out, “Nurse!”

Mercy was already on her way. The surgeons liked her, and asked for her often. She’d begun to preempt them when the pace was wicked like this and a new batch of the near mortally wounded was being sorted for cutting.

She drew the curtain aside, stifled a flinch, and dropped herself into the seat beside the first cot-where one of the remaining doctors was gesturing frantically. “Mercy, there you are. I’m glad it’s you,” he said.

“That makes one of us,” she replied, and she took a bloody set of pincers from his hand, dropping them into the tin bucket at her feet.

“Two of us,” croaked the man on the cot. “I’m glad it’s you, too.”

She forced a smile and said teasingly, “I doubt it very much, since this is our first meeting.”

“First of many, I hope-” He might’ve said more, but what was left of his arm was being examined. Mercy thought it must be god-awful uncomfortable, but he didn’t cry out. He only cut himself off.

“What’s your name?” she asked, partly for the sake of the record, and partly to distract him.

“Christ,” said the doctor, cutting away more of the man’s shirt and revealing greater damage than he’d imagined.

The injured man gasped, “No, that’s not it.” And he gave her a grin that was tighter than a laundry line. “It’s Henry. Gilbert Henry. So I just go by Henry.”

“Henry, Gilbert Henry, who just goes by Henry. I’ll jot that down,” she told him, and she fully intended to, but by then her hands were full with the remains of a sling that hadn’t done much to support the blasted limb-mostly, it’d just held the shattered thing in one pouch. The arm was disintegrating as Dr. Luther did his best to assess it.

“Never liked the name Gilbert,” the man mumbled.

“It’s a fine name,” she assured him.

Dr. Luther said, “Help me turn him over. I’ve got a bad feeling about-”

“I’ve got him. You can lift him. And, I’m sorry, Gilbert Henry”-she repeated his name to better remember it later-“but this is gonna smart. Here, give me your good hand.”

He took it.

“Now, give it a squeeze if we’re hurting you.”

“I could never,” he insisted, gallant to the last.

“You can and you will, and you’ll be glad I made the offer. You won’t put a dent in me, I promise. Now, on the count of three,” she told the doctor, locking her eyes to his.

He picked up the count. “One . . . Two . . .” On three, they hoisted the man together, turning him onto his side and confirming the worst of Dr. Luther’s bad feelings.

Gilbert Henry said, “One of you, say something. Don’t leave a man hanging.” The second half of it came out in a wheeze, for part of the force of his words had leaked out through the oozing hole in his side.

“A couple of ribs,” the doctor said. “Smashed all to hell,” he continued, because he was well past watching his language in front of the nurses, much less in front of Mercy, who often used far fouler diction if she thought the situation required it.

“Three ribs, maybe,” she observed. She observed more than that, too. But she couldn’t say it, not while Gilbert Henry had a death grip on her hand.

The ribs were the least of his problems. The destroyed arm was a greater one, and it would certainly need to be amputated; but what she saw now raised the question of whether or not it was worth the pain and suffering. His lung was pierced at least, shredded at worst. Whatever blast had maimed him had caught him on the left side, taking that arm and tearing into the soft flesh of his torso. With every breath, a burst of warm, damp air spilled out from amid the wreckage of his rib cage.

It was not the kind of wound from which a man recovered.

“Help me roll him back,” Dr. Luther urged, and on a second count of three, Mercy obliged. “Son, I’ve got to tell you the truth. There’s nothing to be done about that arm.”

“I . . . was . . . afraid of that. But, Doc, I can’t hardly breathe. That’s the ribs . . . ain’t it?”

Now that she knew where to look, Mercy could see the rhythmic ooze above his ribs, fresher now, as if the motion of adjusting him had made matters worse. Gilbert Henry might have a couple of hours, or he might have a couple of minutes. But no longer than that, without a straight-from-God’s-hand miracle.

She answered for the doctor, who was still formulating a response. “Yes, that’s your ribs.”

He grimaced, and the shredded arm fluttered.

Dr. Luther said, “It has to go. We’re going to need the ether.”

“Ether? I’ve never had any ether before.” He sounded honestly afraid.

“Never?” Mercy said casually as she reached for the rolling tray with the knockout supplies. It had two shelves; the top one stocked the substance itself and clean rags, plus one of the newfangled mask-and-valve sets that Captain Sally had purchased with her own money. They were the height of technology, and very expensive. “It’s not so bad, I promise. In your condition, I’d call it a blessed relief, Mr. Gilbert Henry.”

He grasped for her hand again. “You won’t leave me, will you?”

“Absolutely not,” she promised. It wasn’t a vow she was positive she could keep, but the soldier couldn’t tell it from her voice.

His thin seam of a grin returned. “As long as you’ll . . . be here.”

The second tray on the rolling cart held nastier instruments. Mercy took care to hide them behind her skirt and apron. He didn’t need to see the powered saw, the twisting clamps, or the oversized shears that were sometimes needed to sever those last few tendons. She made sure that all he saw was her professional pleasantness as she disentangled her fingers and began the preparation work, while the doctor situated himself, lining up the gentler-looking implements and calling for extra rags, sponges, and a second basin filled with hot water-if the nearest retained man could see to it.

“Mercy,” Dr. Luther said. It was a request and a signal.

“Yes, Doctor.” She said to Gilbert Henry, “It’s time, darling. I’m very sorry, but believe me, you’ll wake up praising Jesus that you slept through it.”

It wasn’t her most reassuring speech ever, but on the far side of Gilbert Henry were two other men behind the curtain, each one of whom needed similar attention; and her internal manufacturer of soothing phrases was not performing at its best.

She showed him the mask, a shape like a softened triangle, bubbled to fit over his nose and mouth. “You see this? I’m going to place it over your face, like so-” She held it up over her own mouth, briefly, for demonstrative purposes. “Then I’ll tweak a few knobs over here on this tank-” At this, she pointed at the bullet-shaped vial, a little bigger than a bottle of wine. “Then I’ll mix the ether with the stabilizing gases, and before you can say ‘boo,’ you’ll be having the best sleep of your life.”

“You’ve . . . done this . . . before?”

The words were coming harder to him; he was failing as he lay there, and she knew-suddenly, horribly-that once she placed the mask over his face, he wasn’t ever going to wake up. She fought to keep the warm panic out of her eyes when she said, “Dozens of times. I’ve been here a year and a half,” she exaggerated. Then she set the mask aside and seized the noteboard that was propped up against his cot, most of its forms left unfilled.

“Nurse?” Dr. Luther asked.

“One moment,” she begged. “Before you start napping, Gilbert Henry who’d rather be called just Henry, let me write your information down for safekeeping-so the nurse on the next shift will know all about you.”

“If you . . . like, ma’am.”

“That’s a good man, and a fine patient,” she praised him without looking at him. “So tell me quickly, have you got a mother waiting for you back home? Or . . . or,” she almost choked. “A wife?”

“No wife. A mother . . . though. And . . . a . . . brother, still . . . a . . . boy.”

She wondered how he’d made

it this far in such bad shape-if he’d clung to life this long purely with the goal of the hospital in mind, thinking that if he made it to Robertson, he’d be all right.

“A mother and a little brother. Their names?”

“Abigail June. Maiden . . . name . . . Harper.”

She stalked his words with the pencil nub, scribbling as fast as she could in her graceless, awkward script. “Abigail June, born Harper. That’s your mother, yes? And what town?”

“Memphis. I joined . . . up. In Memphis.”

“A Tennessee boy. Those are just about my favorite kind,” she said.

“Just about?”

She confirmed, “Just about.” She set the noteboard aside, back up against the leg of the cot, and retrieved the gas. “Now, Mr. Gilbert Henry, are you ready?”

He nodded bravely and weakly.

“Very good, dear sir. Just breathe normally, if you don’t mind-” She added privately, And insofar as you’re able. “That’s right, very good. And I want you to count backwards, from the number ten. Can you do that for me?”

His head bobbed very slightly. “Ten,” he said, and the word was muffled around the blown glass shape of the mask. “Ni . . .”

And that was it. He was already out.

Mercy sighed heavily. The doctor said quietly, “Turn it off.”

“I’m sorry?”

“The gas. Turn it off.”

She shook her head. “But if you’re going to take the arm, he might need-”

“I’m not taking the arm. There’s no call to do it. No sense in it,” he added. He might’ve said more, but she knew what he meant, and she waved a hand to tell him no, that she didn’t want to hear it.

“You can’t just let him lie here.”

“Mercy,” Dr. Luther said more tenderly. “You’ve done him a kindness. He’s not going to come around again. Taking the arm would kill him faster, and maim him, too. Let him nap it out, peacefully. Let his family bury him whole. Watch,” he said.

She was watching already, the way the broad chest rose and fell, but without any rhythm, and without any strength. With less drive. More infrequently.

The doctor stood and wrapped his stethoscope into a bundle to jam in his pocket. “I didn’t need to listen to his lungs to know he’s a goner,” he explained, and bent his body over Gilbert Henry to whisper at Mercy. “And I have three other patients-two of whom might actually survive the afternoon if we’re quick enough. Sit with him if you like, but don’t stay long.” He withdrew, and picked up his bag. Then he said in his normal voice, “He doesn’t know you’re here, and he won’t know when you leave. You know it as well as I do.”

She stayed anyway, lingering as long as she dared.

He didn’t have a wife to leave a widow, but he had a mother somewhere, and a little brother. He hadn’t mentioned a father; any father had probably died years ago, in the same damn war. Maybe his father had gone like this, too-lying on a cot, scarcely identified and in pieces. Maybe his father had never gotten home, or word had never made it home, and he’d died alone in a field and no one had even come to bury him for weeks, since that was how it often went in the earlier days of the conflict.

One more ragged breath crawled into Henry’s throat, and she could tell-just from the sound of it, from the critical timbre of that final note-that it was his last. He didn’t exhale. The air merely escaped in a faint puff, passed through his nose and the hole in his side. And the wide chest with the curls of dark hair poking out above the undershirt did not rise again.

She had no sheet handy with which to cover him. She picked up the noteboard and set it facedown on his chest, which would serve as indicator enough to the next nurse, or to the retained men, or whoever came to clean up after her.

“Mercy,” Dr. Luther called sharply. “Bring the cart.”

“Coming,” she said, and she rose, and arranged the cart, retrieving the glass mask and resetting the valves. She felt numb, but only as numb as usual. Next. There was always another one, next.

She swiveled the cart and positioned it at the next figure, groaning and twisting on a squeaking cot that was barely big enough to hold him. Once more, she pasted a smile in place. She greeted the patient. “Well, aren’t you a big son of a gun. Hello there, I’m Nurse Mercy.”

He groaned in response, but did not gurgle or wheeze. Mercy wondered if this one wouldn’t go better.

She retrieved his noteboard with its unfilled forms and said, “I don’t have a name for you yet, dear. What’d your mother call you?”

“Silas,” he spit through gritted teeth. “Newton. Private First Class.” His voice was strong, if strained.

“Silas,” she repeated as she wrote it down. Then, to the doctor, “What are we looking at here?”

“Both legs, below the knee.”

And the patient said, “Cannonball swept me off my feet.” One foot was gone altogether; the second needed to go right after it, as soon as possible.

“Right. Any other pains, problems, or concerns?”

“Goddammit, the legs aren’t enough?” he nearly shrieked.

She kept her voice even. “They’re more than enough, and they’ll be addressed.” She met his eyes and saw so much pain there that she retreated just a little, enough to say, “Look, I’m sorry, Mr. Newton. We’re only trying to get you treated.”

“Oh, I’ve been treated, all right. Those sons of bitches! How am I going to run a mill like this, eh? What’s my wife going to think when I get home and she sees?”

She set the noteboard down beside the cot. “Well, all God’s children got their problems. Here . . .” She pulled a filled syringe off the second tier of the rolling cart and said, “Let me give you something for the pain. It’s a new treatment, but the soldiers have responded to this better than the old-fashioned shot of whiskey and bullet to bite on-”

But he smacked her hand away and called her a name. Mercy immediately told him to calm down, but instead he let his hands flail in every direction, as if he desperately needed someone to hit. Dr. Luther caught one hand and Mercy caught the other. This wasn’t their first unruly patient, and they had a system down. It wasn’t so different from hog-tying, or roping up a calf. The tools were different, but the principle was the same: seize, lasso, fasten, and immobilize. Repeat as necessary.

She twisted one of his beefy arms until another inch would’ve unfastened the bones in his wrist; and then she clapped a restraining cuff from the tray down upon it. With one swift motion, she yanked the thusly adorned wrist down to the nearest leg of the cot, and secured the clip to hold him in place. If Dr. Luther hadn’t been performing pretty much the same technique on the other wrist, it wouldn’t have held up longer than a few seconds.

But the doctor’s restraints were affixed a moment after Mercy’s. Then they were saddled with one violently unhappy man, pinioned to a cot and thrashing in such a manner that he was bound to injure himself further if he wasn’t more elaborately subdued.

Mercy reached for the mask, spun the knob to dispense the ether, and shoved it over Silas Newton’s face, holding him by the chin to keep him from shaking his head back and forth and eluding the sedation. Soon his objections softened and surrendered, and the last vestiges of his refusal to cooperate were overcome.

“Jackass,” Mercy muttered.

“Indeed,” said Dr. Luther. “Get his shoe off for me, would you, please?”

“Yes sir,” she said, and reached for the laces.

Over the next three hours, the doctor’s predictions were borne out. Two of the remaining three men survived, including the disagreeable Silas Newton. In time, Mercy was relieved by the severe and upstanding Nurse Esther Floyd, who hauled the young Nurse Sarah Fitzhugh along in her wake.

Mercy left the bloody beds behind the curtain and all but staggered back into the main ballroom grounds, where most of the men had at least been seen, if not treated and fed quite yet. Stumbling past them and around them, she stopped a few times when someone tugged at her

passing skirt, asking for a drink or for a doctor.

Finally she found her way outside, into the afternoon that was going gold and navy blue at the edges, and would be nearly black before long.

She’d missed supper, and hadn’t noticed.

Well. She’d pick something up in a few minutes-whatever she could scavenge from the kitchen, even though she knew good and well it’d be pretty much nothing. Either you ate as soon as you were called, or you didn’t eat. But it’d be worth looking. She might get lucky and find a spare biscuit and a dab of butter, which would fill her up enough to let her sleep.

She was almost to the kitchen when Paul Forks, the retained man, said her name, stopping her in the hallway next to the first-floor entry ward. She put one hand up on the wall and leaned against it that way. Too worn out to stand still, she couldn’t hold herself upright anymore unless she kept moving. But she said, “Yes, Mr. Forks? What is it?”

“Begging your pardon, Nurse Mercy. But there’s a message for you.”

“A message? Goddamn. I’ve had about enough of messages,” she said, more to the floor than to the messenger. Then, by way of apology, she said, “I’m sorry. It’s not your fault, and thanks for flagging me down.”

“It’s all right,” he told her, and approached her cautiously. Paul Forks approached everyone cautiously. It could’ve been a long-standing habit, or maybe it was a new thing, a behavior acquired on the battlefield.

He went on to say, “It came Western Union.” He held out an envelope.

She took it. “Western Union? You can’t be serious.” She was afraid maybe it was another message repeating the same news she’d received the day before. The world was like that sometimes. No news for ages, and then more news than you can stand, all at once. She didn’t want to read it. She didn’t want to know what it said.

“Yes ma’am, very serious. The stamp on the outside says it came from Tacoma, out in Washington-not the one next door, but the western territory. Or that’s where the message started, anyhow. I don’t know too well how the telegraph works.”

Maplecroft

Maplecroft Chapelwood

Chapelwood Fathom

Fathom Hellbent

Hellbent Jacaranda

Jacaranda Four and Twenty Blackbirds

Four and Twenty Blackbirds Dreadnought

Dreadnought Dreadful Skin

Dreadful Skin Bloodshot

Bloodshot Tanglefoot

Tanglefoot Clementine

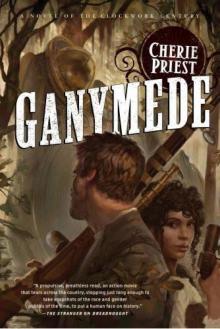

Clementine Ganymede

Ganymede The Inexplicables

The Inexplicables Not Flesh Nor Feathers

Not Flesh Nor Feathers Wings to the Kingdom

Wings to the Kingdom Fiddlehead

Fiddlehead Tanglefoot: A Story of the Clockwork Century

Tanglefoot: A Story of the Clockwork Century The Agony House

The Agony House Ganymede (Clockwork Century)

Ganymede (Clockwork Century) The Inexplicables (Clockwork Century)

The Inexplicables (Clockwork Century) Clementine tcc-2

Clementine tcc-2 Grants Pass

Grants Pass Dreadnought tcc-3

Dreadnought tcc-3 Ganymede tcc-4

Ganymede tcc-4