- Home

- Cherie Priest

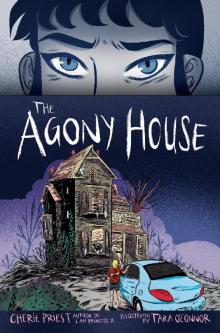

The Agony House Page 3

The Agony House Read online

Page 3

“My undying …” She stopped herself. Her undying what? Gratitude? Affection? Nothing sounded right, so she let it go with, “… remembrance.”

He winked, and reached into his pocket for some change for the machine. “Hey, I’ll take it.”

Before she could embarrass herself any worse, she fled for the counter and caught Mike as he was checking out. When they were finished paying, she helped him load up the car. All the while, he very studiously avoided asking any questions. Denise couldn’t stand it, so when they were inside the Kia and the doors were shut, she broke the ice. “Since I know you’re dying to ask, his name is Norman. He swapped me out a decent dollar for one of your crummy dollars.”

“Look at you, making friends already.”

“Dude, I’ll probably never see that guy again.”

“He’s a cute kid, though.”

She rolled her eyes and leaned her head back against the seat. “Please do not ever call any guy cute again. You’re making it weird. Weirder. I already made it weird enough.”

“Okay, okay. I’ll try to keep from making it weirder. You’ve obviously got that part under control.”

The electrician came around later that day. She went on for fifteen minutes about how ancient the house’s wiring was, and how many expensive-sounding code violations they would have to fix eventually—but then she flipped some breakers, tested some wires, rearranged some connections, replaced some fuses … and restored power to the second story of the Agony House.

Sure, they’d need another week’s worth of electrical work before too long, but hey. It was a start.

With AC now wafting weakly through all the rooms, livable and unlivable alike, the small family sat down to another fast-food meal. They’d cleared out the dining room and set up the left-behind chairs, and it almost looked like civilized people lived there. The sun was going down; there was light enough to see by, but when the shadows stretched out long and low, Mike pulled out a lamp and plugged it in.

They all sat around feeling fat and almost happy, leaning back in those spindly seats and licking the last bits of chicken grease from their fingers, until Sally gestured with a french fry and warned, “You two know it won’t always be like this, don’t you? Enjoy the junk food now, because I’m going shopping tomorrow. We’ll have real meals on a regular schedule, like normal.”

Denise asked, “Will we ever get the kitchen to … I don’t know. Work?”

“Oh, come on. It’s not that bad in there,” her mother scoffed. “For Chrissake, honey—it’s no worse than that place on Elgin Street.”

Mike frowned quizzically. He’d never seen the Elgin house.

Denise told him, “We only lived there for a year, after Mom lost that job—when the restaurant folded. It was pretty bad.”

“When was this?”

She shrugged. “Not long before she met you.”

It wasn’t the world’s most romantic meeting—trapped in a stalled and sweltering METRO light-rail train, waiting for the service crews to let them out. But love grows in the strangest places, like a bluebell on a cow pie. Or so her new Uncle James had declared in the best man’s toast, when he’d recalled the story for the sake of the audience.

“No, it was at least a couple of years before Mike,” her mother insisted. “Because after Elgin, we ended up a few miles away, on Burkett—and that wasn’t much better, but at least it was clean. After that, we lucked into that place in Old Chinatown. That one wasn’t so bad.”

“What she means to say, Mike, is that we’ve lived in some real dumps.”

Sally and Mike spoke at exactly the same time. She said, “It’s not a dump!” and he said, “It won’t be a dump forever!” They turned and giggled at each other like they’d done something cute.

Denise rolled her eyes. “But look at all this. It can’t be healthy … ?” she tried, using a straw to point at the holes, the stains, and the dark patches they hadn’t gotten to yet, all of them probably made of deathly black mold. She was sure of it.

Sally said, “We’ll make it healthy. We’ll do the big stuff first—the rewiring and plumbing, and then the roof. The rest of it, we can do ourselves with some elbow grease.”

“And money.”

Like her mom needed reminding. The loan had come with funds to fix the place up and trick it out as a proper business, ready to host and feed out-of-towners, but the money would come in bits and pieces, gradually doled out as the house was brought up to code. They could only have a chunk of it at a time. It was supposed to protect the bank from a risky investment, but it felt like a dirty trick.

“We have some money,” Sally insisted.

Denise pushed. “But is it enough money?”

“It’s always enough, baby. One way or another. It’s always enough.”

“Technically you’re right. I mean, in the sense that we haven’t died of starvation or exposure. Yet.”

Mike laughed at the pair of them. “Denise, if your mom wanted to whip this house into shape all by herself, I do believe she could. But it’s not just her, all by herself with a little girl anymore. Now it’s us, all together. Three adults, more or less.”

“Um, I’m eight months shy of ‘adult,’ ” Denise pointed out. “I have eight more months to screw up big-time, and still get off as a juvenile.”

Sally shook her head with mock exasperation. “What a terrible way to look at a birthday.”

“It’s a perfectly practical way of looking at it,” she argued.

Mike rose from his seat and wadded up his trash, then stuffed it into the takeout bag. “I hope you aren’t planning a last-minute crime spree. When college applications ask about your extracurricular activities, they don’t mean armed robbery.”

“Courts seal juvenile records, you know.”

“Yeah, and I wish you didn’t.” Sally gathered her own trash and produced a plastic garbage bag to collect it all. “Here, give me your stuff. We’ve sat around on our butts long enough.”

Together they picked up after supper, and Mike produced a speaker set for his iPhone. That could only mean one thing: a terrible evening of music that quit making the radio rounds before Denise was born. He hunkered over the screen and scrolled through his playlist.

“Mike, I love you, man—but it’s been a long day, and I can’t handle whatever weird old stuff you’re queuing up.”

“Aw, you love me?”

“Well, I like you enough to let you stay … but I’ve gotta go work on my room. Y’all have fun down here, doing the fox-trot or peace-ing out, or whatever it is you old folks do when I’m not looking.”

Denise headed for the big box of cleaning supplies in the kitchen. She rummaged through it and made her selections, tossing them into the bucket. She snagged the broom too. She tucked it under her arm and stomped up the stairs, flipping light switches as she went.

It was getting good and dark outside, and after twilight, the second floor hallway was practically a tomb. It had nothing to let in natural light except a small window at the far end, so even in the middle of the day with all the doors open, it was pretty bleak. Once the sun went down, you were screwed without a lamp.

The fixture over the stairs worked, or it mostly worked. It was a square glass shade that housed four bulbs, but only one was lit up. Another lamp at the far end of the hall sputtered and warmed, but it mostly just hung out on the ceiling looking sad and yellow.

Downstairs, Mike found his groove and turned it up, sending shouty 1980s white-guy hip-hop drifting up the stairs.

Denise didn’t know the group, and she was entirely unprepared to admit that it sounded kind of fun, so she disappeared into her room. The ceiling fan came on when she flipped the switch. The fan had space for three bulbs in three flower-shaped glass shades. Two of the three beat the odds and lit up on cue.

The room looked better by the dim, fuzzy light of the old-fashioned incandescent bulbs—but only a little. It was harder to see the dust bunnies and cobwebs without the sun streami

ng in, but Denise wasn’t fooled. She still knew that it was the best of the worst, and that was all.

She heard a chime and felt a buzzing in her shorts.

She jumped like she’d been shocked, then fumbled her phone out of her back pocket. “Trish!” she yelped. The text message read: NEW DIGS HOT OR NOT LOL? Before she could unlock the phone for a reply, a second one landed on its heels: y so quiet ru ok?

Her thumbs got into gear, and she hastily replied: I’m quiet? Haven’t heard from u since I left.

liarpants, quoth Tricia. Oh wait my phone is

Denise sat down on the floor cross-legged, and tapped back: ur phone is???

I have like 50 texts dint go thru sry

She smiled down at the screen. Thought you didn’t love me anymore.

Then she leaned back against the wall and tried not to think of how grimy it was, or how the plaster was soft with water and mold. She settled down instead and thumb-typed at lightning speed—giving Trish a quick rundown on the move, and the heat, and the house she was now forced to call home. Then she mentioned Norman, named for an aunt. Since he was the only person she’d met so far, and she was running out of subjects that didn’t sound like whining.

It was a relief to talk to anybody back in familiar old Texas, even if talking was just keyboard swiping, and trying to win a game of Who Can Find the Most Ridiculous Emoji. Poop-coil in a party hat with fireworks usually won, but Trish showed up with a brown beard smoking a cigar and holding a martini glass, and Denise admitted defeat.

How’s Kieron? Is he ok or still weird? she asked as an afterthought.

Not as weird as ur super-proper texts but still weird. I hrd he has a new gurl.

Super-proper, but u alwys understand me. She hit SEND before either she or autocorrect caught the typo, and scowled at it, but she refused to be embarrassed about cautious texting. She’d once read about a court case that happened over a comma in a contract. You could never be too careful.

Did u read me? Kieron has a new um-friend. Like this is my, um, friend.

She didn’t really care, but she was curious. ORLY?

Sophomore. 2 young 2 no better I guess.

Denise laughed. She’ll learn.

So tell me about this house of yours its haunted as crap, right

Her thumbs hovered over the screen. She thought about mentioning the attic door, but that’d be silly. It hadn’t been anything at all. What would she say? “I opened a door and it smelled bad.” That wasn’t a ghost story, and Trish wanted a ghost story.

Haunted as crap, she typed in return. Crappy as crap, 4 sure.

PICS OR GET OUT

She realized she hadn’t taken any. She hadn’t thought about it, or hadn’t wanted to. Maybe in the back of her head, she was too embarrassed at the thought of anybody else seeing this place, and knowing she lived there. But she really ought to take some in the light of day—for the sake of a good before-and-after, if it all worked out someday. Or to show how narrowly she’d escaped death by debris, if it didn’t.

Don’t have any.

SNAP ME SOME. DOO EET.

Later, she promised. She wasn’t sure if she meant it or not. Busy right now. Unpacking. Getting my bedroom set up.

OK BUT L8R

I PROMISE

When Trish didn’t respond in a few seconds, she put the phone aside. Their chat had run on long enough, and the phone’s battery was low—so Denise pulled the charger cord out of the messenger bag she typically used for a purse. Of the three outlets in her room, only one worked, and it took her a few minutes to find it. She chalked it up to one more thing on the list of Things That Suck About the Agony House.

Maybe she really should keep a list … or maybe she should make some effort to have a life, because keeping track of all the house’s failings could turn into a full-time job. Technically, she could afford a part-time job. Summer had just begun.

But where would she work? Doing what? The house was sure to eat her life for the next couple of months.

Besides, come fall she’d be headed for that school they’d passed earlier today. It was one of New Orleans’s new “recovery zone” charter schools, where she wouldn’t know a single soul.

She sat down beside the phone and leaned her head back against the wall. She hated the thought of a new school for her senior year. It made all the celebration of her PreACT and PSAT scores feel moot. Her stellar numbers and top-notch grades had brought some great college recruiters sniffing around, but their offers would all depend on good scores on the real thing and a strong finishing GPA. Would this year be a string of easy A grades, or would it be a miserable slog that felt like a personal vendetta?

Nothing was in the bag just yet. Like her old gymnastics coach used to say, she still had to stick the landing.

She was glad to see her mom happy—she truly was, and not even in a bitter way. It felt like it had been Sally and Denise Versus the World since forever, since the Storm. But it also felt like someone had pitched a grenade into her life now, right when she was finally building up some momentum. Now it was time to start all over again.

“This is going to suck,” she told the ceiling.

The ceiling didn’t argue with her.

She closed her eyes and listened to the bouncy music playing downstairs, dulled by the floorboards but chipper-sounding all the same. Mike said something, but Denise couldn’t make it out. Her mother laughed, and the music played on. They were definitely happy, and that was something.

It would’ve been really, really great if Denise got to be happy too, but she already knew the world didn’t work that way. Sometimes, you had to take turns.

She gave up and got up, and used the duster to swab the fourth corner clean of spiderwebs. One spider took offense, and scuttled across the ceiling—disappearing into a crack in the plaster. Then she took the broom for a half-hearted spin around the floor, but she hadn’t brought a dustpan with her, so she just turned off the box fan and swept all the dust and junk out into the hall. “Screw it,” she said to the puff of debris as it settled on the floor. “Nobody cares, anyway.”

The fixture at the top of the stairs rattled as if offended. Denise frowned at it, but it kept jiggling anyway—like someone was jumping up and down on the floor above it. But no one was up there in the attic, or that’s what she assured herself because she sure as hell wasn’t about to go look.

The glass shade trembled, and the lone illuminated bulb twitched in its socket. It flared, sparked, and went out with an angry poof.

The hallway dimmed. At the other end of the corridor, the lone yellow bulb was so dull that you could hardly tell if it was on or not. The rest of the light filtered up from downstairs or out from Denise’s bedroom. She stood in the doorway, holding the broom and casting a narrow shadow onto the dirty carpet runner.

Without the weak light from the fixture, the hall felt close and crowded.

Denise listened hard, focusing on some faint noise that played above Mike’s music, or around it: a low-pitched buzzing, like the sound another failing bulb (or a wasp) would make. No, not that. Not exactly. A vague rushing, like water running from a tap.

No, not that, either.

It was both quieter and more deliberate—and when Denise closed her eyes, she thought she heard a woman humming a song. She couldn’t make out the tune, not with Mike’s music going to town downstairs, and her mother talking and laughing. They were dancing in the parlor, she thought. Their feet were circling, jumping. Playing hopscotch with the holes in the floor.

Maybe that’s all it was, rattling the lamp—only the newlyweds, being happy together.

The discordant humming grew louder, and the song came clearer—but she didn’t recognize it. Was it her mother, singing along to the wrong track? She didn’t think so. Louder and louder, and this wasn’t Sally’s voice at all. This wasn’t what it sounded like when she murmured a lullaby, or the lyrics to something old and dorky.

Denise opened her eyes and the humming stopped.

Just like that.

She blinked hard, and rubbed her knuckles against her eyelids. The weird singing was gone, but it’d left something behind: There, on the floor, in the dust she’d cast out of her bedroom … a very distinct set of marks had appeared. They marched in delicate pairs—footprints, too small to be a man’s, and not small enough to be a child’s. They came from the top of the stairs.

No, that wasn’t true. They came from the attic door, and they pattered right up to Denise, stopping in front of her—not eight inches away from the tips of her toes.

No, that wasn’t true, either. When she turned around she saw that the footprints kept going, the pointed shapes strolling into her bedroom, tracking the dust back from where it’d come.

And then vanishing.

Denise’s gaze went wild, back and forth from the attic door to the bedroom—where there wasn’t any dust to leave any tracks, and there wasn’t anybody standing, singing a song. The room was as empty as before, and there was nowhere to hide. Only a few boxes were stacked, and those were against the wall. The closet was full of hanging clothes, and it still didn’t have a door. “A door,” she whispered hoarsely. It was a frantic thought, and she held it like a tiny lifeline of rational truth. “I need a door.”

She needed a lot of things. She needed a glass of water and a shower. She needed to assemble her bed frame, unless she wanted to keep sleeping on a mattress and box spring flat on the floor—and maybe she did want to sleep that way, just for the night. When the bed was on the floor, there was nothing underneath it. When the bed was on the ground, there was nowhere for anybody to hide—even an invisible, softly singing anybody who left behind a funny smell. Not a bad one. Just a funny one.

Denise sniffed for clues and picked up something sharp but sweet. It could’ve been the scent of cleaning products, perhaps, or the bottle of shower gel she’d left beside the tub. The bathroom door was open, right around the corner.

She sniffed again.

No, it wasn’t gardenia soap lingering in the air. It smelled more like roses, mixed with something else. Some kind of perfume, something an old lady would spritz all over herself before heading to church.

Maplecroft

Maplecroft Chapelwood

Chapelwood Fathom

Fathom Hellbent

Hellbent Jacaranda

Jacaranda Four and Twenty Blackbirds

Four and Twenty Blackbirds Dreadnought

Dreadnought Dreadful Skin

Dreadful Skin Bloodshot

Bloodshot Tanglefoot

Tanglefoot Clementine

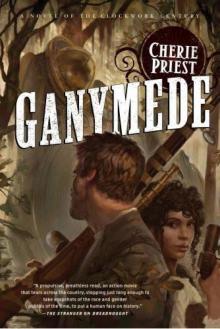

Clementine Ganymede

Ganymede The Inexplicables

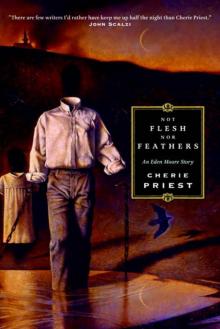

The Inexplicables Not Flesh Nor Feathers

Not Flesh Nor Feathers Wings to the Kingdom

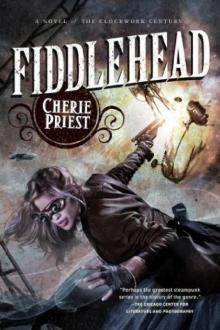

Wings to the Kingdom Fiddlehead

Fiddlehead Tanglefoot: A Story of the Clockwork Century

Tanglefoot: A Story of the Clockwork Century The Agony House

The Agony House Ganymede (Clockwork Century)

Ganymede (Clockwork Century) The Inexplicables (Clockwork Century)

The Inexplicables (Clockwork Century) Clementine tcc-2

Clementine tcc-2 Grants Pass

Grants Pass Dreadnought tcc-3

Dreadnought tcc-3 Ganymede tcc-4

Ganymede tcc-4