- Home

- Cherie Priest

Chapelwood Page 4

Chapelwood Read online

Page 4

If she doesn’t, perhaps by tomorrow afternoon I’ll go over to Chapelwood myself. Into the pit of vipers, yes, but I have the cross on my side, and a promise to fulfill. The girl needs me.

God, she needs someone.

• • •

I’ve spent the last few weeks collecting information on this strange church in the forest, on the reverend’s old estate.

There isn’t much to collect, I’ll be honest—what I’ve found through public records amounts to a hill of beans. Chapelwood is registered with the county as a Christian congregation, under the banner “Disciples of Heaven,” which is as vague and meaningless a description as I’ve ever heard. Is it formally authorized to perform weddings and baptisms, all the ordinary things I can do here at Saint Paul’s? Yes. The property was once part of a private farm, which was sold off piecemeal after the war, and Reverend Davis’s father purchased the bulk of it.

(I think the church Ruth describes might actually be the original farmhouse, strangely augmented over the years. Or then again, maybe it’s one of the barns, having undergone a conversion of its own.)

It is now privately owned by the reverend, though parts of the surrounding property are held in trust by a private firm . . . and on the board of this firm, I’ve spotted two names that are prominent in the Klan, and three others you’ll find in the front row of every True Americans meeting.

The coincidences are piling up. The overlap, I mean . . . between Birmingham’s corrupt politics and the Chapelwood Estate.

It might well be argued that bigots sit at the top of the power structure here, and so you might well expect to find them at the top of the churches, the businesses, and the political heap. But these newer groups, the True Americans and their Guardians of Liberty in particular . . . their rise coincides with this sinister place of worship.

I may believe in divine contrivance, but I don’t believe in coincidences.

(Yes, I think there’s a difference.)

My notes are thin on the ground, but I’ll make a point to send them east, regardless—to Boston, and an old friend of mine there. He’s an inspector, that’s all I’ll say about his job. A man about my age, or a little younger, with a head for peculiar facts and a nose for the weird.

Then again, maybe I ought to restrain myself. I’ve been sending him letters and clippings on the axe murders since the start of August, and I’ve heard nothing from him in return. He could be off on a case, and therefore out of the office. I hope he’s well, at any rate. I’m sure I’ll hear from him soon enough. He’s not the kind to leave a man waiting, not on purpose.

I’d like to see him again. He’s a jovial fellow, as strange as the Good Lord ever dared to make one—but a stalwart friend in times of difficulty. He’s also tough to scare, and I could use his stouthearted assistance right about now.

Well, if the axe murders aren’t enough to lure him out for a visit, I’m sure the Chapelwood matter will bring him around. I sense that it’s more to his taste.

Ruth Stephenson

SEPTEMBER 19, 1921

I shouldn’t have done it, but I’m glad I did.

Daddy wasn’t home—he’d headed off to a “prayer meeting” and left me with Momma to set up supper for him. It wasn’t quite dark yet, but dark was coming, and we had just turned all the lights on and fired up the stove when my momma saw the neighbor’s dog digging in our backyard garden. She’s been swearing and throwing shoes at that dog for ages, and it made her mad to see him stroll right on up and start making a mess—so this time, she took off her apron, threw it on the table, and said she was going to go smack that thing silly.

I didn’t really think she’d catch it, but it was halfway funny watching her try. She ran around the yard with a rake, swiping it back and forth, never noticing that the dog was having a grand old time. He figured they were playing a game, and she figured she was going to beat him blue, and maybe go over to Mr. Marks and start swinging at him, too, since it was his dog after all.

Not much has been very funny, lately. Not halfway, or even a quarter way. Birmingham has become a city full of men in hoods, or men with axes. It’s a place where dark churches swallow people up whole. It’s not a place where too much happens to make you smile.

So I watched her for a minute, and then I heard something.

A thump, and maybe a sliding noise, like something heavy being dragged around. I tried to tell myself it was my imagination, because that’s what you ought to do when you know you’re inside a house by yourself—but you hear something heavy moving around in your momma and daddy’s bedroom. Their bedroom . . . that’s where it was coming from. There was something in there. I listened hard, and it wasn’t my imagination at all. And it wasn’t funny, neither.

It wasn’t no happy dog playing tag. It wasn’t my sister, because she had the good sense to be married and living someplace else. It wasn’t anybody.

It didn’t sound like a person, anyway.

It’s hard to explain, but I felt that weird thing again, that dizzy feeling I’ve been getting a lot, especially since Daddy started dragging us all to Chapelwood. Almost like I’m sick, but not quite. Almost like I’ve been spinning around with my arms out, or hanging on to the merry-go-round while a big man shoves it faster and faster, and it spins so hard, so fast, that it almost throws me off into the sky.

Momma calls them my little spells, and says it’s nothing to worry about, even when I tell her I can hear her long-dead momma trying to tell me something from someplace far away. But she’s got her blinders on so thick, it’s a wonder she can see the end of her own nose. Whatever’s going on, she either knows and doesn’t care, or she can’t see it, for not paying attention. Either way, it’s hard to respect her. It’s hard to trust her, too.

Whatever’s happening, she’s no ally of mine.

• • •

(Father Coyle says I shouldn’t be so hard on her, because it’s not really her fault. I know he’s kind of right, but I don’t think he’s totally right. Sure, she’s gotten used to Daddy and his ways; and yes, I know, she’s doing the best she can to muddle on through this life like everyone else. But at some point, a full-grown woman has to be accountable for her own self, and for the choices she’s made. That’s how I see it. And I see my momma just closing her eyes, and pretending that none of this has ever been her fault, and none of it has ever been up to her. And that just isn’t true. She’s had plenty of chances to choose one thing or another, one person or another, one church or another. But she lets him choose for her, and that’s a choice, too, isn’t it?)

• • •

But I had myself a little spell, and that’s a good way to talk about it, I think.

A spell is a magical thing, and not always a good thing . . . that’s what I learned from the library books I used to sneak home, before Daddy caught me one time too many. My little spells are magical, and they are bad. Like I’ve pricked my finger on a spindle (and I don’t even know what a spindle is, but apparently it’s something sharp) and gone to sleep for a thousand years . . . or that’s what it feels like I’m trying to do.

These spells . . . it’s like there’s a dark fog creeping in, coming at me from all sides, making it hard to see. It sneaks up and wraps itself around my eyes. It feels like the lights have all gone out—I couldn’t see the light on the stove, or the gaslights we had just lit up, even though I could hear them hissing. I knew they were on, but I couldn’t see them.

After a few seconds, I couldn’t really see much of anything. I staggered around, holding on to the chairs to keep myself from falling, and I closed my eyes—because when you can’t see anything, at least it ain’t weird if your eyes are closed, and maybe that’s dumb, but that’s what I thought. So that’s what I did.

Usually, when I have a spell, this is the part where I start hearing voices. Most of the time, it’s nobody I know, but sometimes it’s Grandma or our ne

ighbor Mr. Miller, who died when I was thirteen. I never knew him well when he was alive, so I don’t know why he’s so chatty now that he’s in the ground.

But I didn’t hear any voices. I was all alone with other noise.

I closed my eyes and I saw that sparkling black light—you know, the kind when you’ve held your breath too long, or stood up too fast after being half asleep. Some people say it’s like seeing stars, but it isn’t. The stars don’t move, not in those darting, fizzling patterns. Stars don’t wink on and off, and go out altogether when you shake your head, trying to fling that spell away.

In the big bedroom, I heard it louder and louder: that thump, slide, and drag . . .

I thought I was taking myself away from it, but I must’ve got turned around. I found a doorknob and I turned it, thinking it’d let me outside—and I don’t know why I wanted to get outside, blind like I was from the spell, and from closing my eyes. But I turned the knob and shoved the door and I knew, even without being able to see, that I’d just opened up the bigger bedroom where Momma and Daddy slept.

I opened my eyes, for all the good it did me. I saw only the shadows of their furniture, the bed, the two chifferobes next to each other up against the wall, and a little bedside table where my momma used to keep a Bible—but I bet she doesn’t anymore.

And I saw something else, too. Another shadow, one that shouldn’t have been there. Something about as big and long as an oak root, coming right out of the wall, swaying back and forth along the floor.

I rubbed my eyes and didn’t see anything no clearer, and maybe that was for the best. I didn’t really want to look at it, anyway.

I tried to move away from the thing, to get myself back out of that room, because it was the last place on earth I wanted to be. I found the doorknob behind me, grabbed it, and ran—slamming the door behind me—but then the damnedest thing happened, and it don’t make no sense, but this is what it was: I wasn’t in the parlor, like I oughta’ve been. I was back in the bedroom, or still in the bedroom—I couldn’t say. I was so confused, so scared. All I know is I went through the door and I didn’t go anyplace, and I was just about to stop breathing, I was so afraid.

Then the thing on the floor, the tree root, or snake tail, or whatever it was . . . it came for me.

It took me by the ankle and it wound itself up tight, and I started screaming—but it only squeezed harder until I thought it was going to take my foot off. It slipped up my leg, up to my knee. And the more of me it touched, the more I could see again . . . but what I saw . . . it couldn’t have been real.

I saw stars, when it held me. Real stars, not the fuzzy kind your brain makes. I saw heaven, so far away and so strange . . . it was heaven—it must’ve been. Somewhere out past the clouds, past the stars—they went by me so quick it was like they’d turned into streaks, into long white lines. I was moving through the universe and it was all so bright and so dark, too, that I didn’t even notice I wasn’t breathing anymore. I couldn’t breathe. There wasn’t any air. There was only the feeling of being squeezed all over my whole body, and watching the stars stretch and explode and fade away.

I could hear my daddy’s voice somewhere, even though he wasn’t with me. I heard him and the reverend talking. I heard my momma talking, too, but not to the dog in the yard and not to me. I heard a thousand voices, all up inside my ears, and I was all alone in my parents’ bedroom except for the thing on the floor that I couldn’t see—but I could feel it, and it was trying to tell me something, but I didn’t know what.

That’s true, I think. It was trying to talk to me, using the words of all the people I ever met, ever talked to . . . It took the words from one person, and mixed them up with the words from another person . . . mixing and matching, lining up letters and voices that were so scrambled it was like listening to a thousand preachers all telling different sermons at the same time, as loud as they could.

No, wait. It wasn’t quite so personal as that. It was more like standing in a hall with a thousand Victrolas, each one playing a different record. The words I heard in my head didn’t come from real people, living and speaking. They were just recordings cut up into pieces.

Sweet Jesus, it’s hard to explain.

I caught single words here and there: lost, falling, come, why, drop, star, water, here.

If I hadn’t been so scared spitless, I might have written some of them down—maybe if I could write fast enough, I could catch enough of them to mean something. I’ll start carrying a notebook and a pencil, in case it happens again. (I hope it doesn’t happen again. But if it does, I’ll be ready.)

I don’t know what it wanted, and I don’t know what it was saying, but I felt my whole body going limp from not breathing. I don’t know how long I wasn’t breathing . . . I just plain forgot to do it. But when I remembered—then I took a little breath, and a bigger one. Then a real deep one, and I started screaming my head off.

• • •

If these are little spells, like Momma says, then I broke this one with the screaming. Just remembering to breathe, remembering I could scream and shout and kick and fight . . . it did something. It shook me loose from the thing in the room, and there was this feeling of moving so fast—so fast that it made my skin ripple and my eyes bleed—and there were stars shooting by like gaslights.

And then I was just in the room again, all by myself.

Outside, my momma was calling for me. I guess she heard me yelling.

But I didn’t want to see her or talk to her. I didn’t want her to come after me. I wanted out of that house, and that’s all I wanted.

I still couldn’t see too good, but my sight was coming back. I felt my way to the door, and this time it let me out—it didn’t send me right back in, so yes, this spell, I broke it my own damn self. I’ll remember that next time: I’ll tell myself over and over again, “You just have to breathe, that’s it. Breathe, and then make a whole lot of noise.” (So if there’s a next time, when there’s a next time . . .)

I have a handbag in my room. There’s not much in it, only a little money I’ve earned and some personal things, and a little pocketknife I carry in case I need it. I grabbed it, and I grabbed my coat, even though it wasn’t so cold that I really needed it.

So help me God, I ran.

I ran to the edge of town and right through it, right across it, where the axe murders have been going on for the last year or so, right there down by Five Points where the Italians have their shops and their restaurants, and the Jews have their family banks and their movie theaters, and the girls my age don’t walk home by themselves—or with colored boys, neither, because there are awful men who will hurt you if they catch you together, that’s what everybody says.

I ran and ran, and I just hoped that anybody carrying something so heavy as an axe wouldn’t be able to catch me—but to be real true with myself, I wasn’t that worried about it. I had bigger worries, and stranger things to be scared of than some angry folks with weapons.

So help me God, I ran.

(So help me God. So help us God. So help everybody God, because there’s only so much we can do to help ourselves.)

I ran to Father Coyle because I didn’t know where else I should go, and when I talked my way past the guard with a gun, and got myself up into the sanctuary where he was praying over his candles and his books, he looked real happy to see me.

He gave me some tea and something to eat, and he let me talk. He let me ramble about the Victrolas and the stars, and when I was finished—when I’d run out of words, and sat there shaking . . . then he told me he had an idea.

It was a crazy idea, but these are crazy times and I’ve got nothing better.

So help me God, I’m going to do it.

I’m scared, though.

I don’t think it’s going to be so easy that Daddy will let me go—and Chapelwood will let me leave and never come back—ju

st because I take a husband. The law may respect it, or then again the law may not (around here, you never know), but that church in the woods sure as hell won’t, and my daddy won’t, either.

Father Coyle is a good man, and Saint Paul’s is a good church, and it deserves better than what this city is throwing at it. But people don’t always get what they deserve, now do they? Sometimes they get a lot better, or a lot worse . . . and I’m afraid for how it’s going to go for my friend the priest, once word gets around.

He’s drawing up a wedding license for me, and he’s going to sign it. I’m just praying—to my God and his God, in case they’re listening—that he doesn’t sign his own funeral slip while he’s at it.

He says he’s not worried, that we’ll put ourselves in heaven’s hands, and all things will work together for good. Well, maybe they will, and maybe they won’t, so I’ll worry for the both of us. I’ve seen heaven, I think. It hasn’t got any hands, and I don’t think it cares one way or another how much we trust it.

Inspector Simon Wolf

BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS SEPTEMBER 23, 1921

Axe murders.

Apparently we need one great round of them per century, but at least this time they’ve happened relatively early and well away from New England—taking place down south in these reunited states. This particular spree occurs in Birmingham, Alabama. Named for an Old England city, I suppose, not that it’s much of a connection to anything . . . and there’s no sense in overselling it: These particular axe murders haven’t held any real interest for me, or for the organization that continues to pay my bills—even after all this time, and my habit of offering bombastic, semiannual resignation notices.

These axe murders appear at a glance to be clear and boring as day—small shop owners and assorted pedestrians, often of immigrant stock, terrorized as part of some thuggish racket. Then, after the first few deaths, the demographic broadened to include young couples . . . particularly young couples whose skin tones weren’t quite the same. Another easy guess, not worth too much time: The Klan has not so much a toehold as a choke hold on the city, and likewise it has a grudge against such mismatched unions. The math added up neatly enough. The Birmingham murders were (are?) hardly of sufficient caliber to involve our Quiet Society.

Maplecroft

Maplecroft Chapelwood

Chapelwood Fathom

Fathom Hellbent

Hellbent Jacaranda

Jacaranda Four and Twenty Blackbirds

Four and Twenty Blackbirds Dreadnought

Dreadnought Dreadful Skin

Dreadful Skin Bloodshot

Bloodshot Tanglefoot

Tanglefoot Clementine

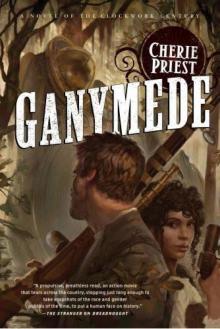

Clementine Ganymede

Ganymede The Inexplicables

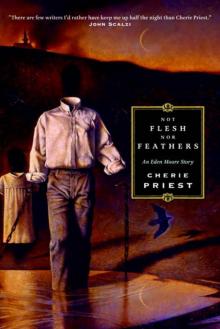

The Inexplicables Not Flesh Nor Feathers

Not Flesh Nor Feathers Wings to the Kingdom

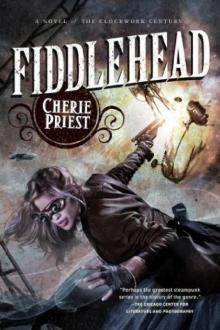

Wings to the Kingdom Fiddlehead

Fiddlehead Tanglefoot: A Story of the Clockwork Century

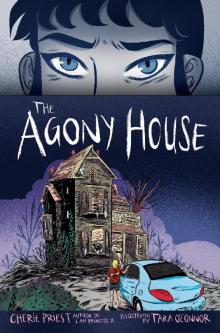

Tanglefoot: A Story of the Clockwork Century The Agony House

The Agony House Ganymede (Clockwork Century)

Ganymede (Clockwork Century) The Inexplicables (Clockwork Century)

The Inexplicables (Clockwork Century) Clementine tcc-2

Clementine tcc-2 Grants Pass

Grants Pass Dreadnought tcc-3

Dreadnought tcc-3 Ganymede tcc-4

Ganymede tcc-4