- Home

- Cherie Priest

Dreadnought tcc-3 Page 9

Dreadnought tcc-3 Read online

Page 9

“Larsen!” Dennis called once more.

This time she smacked him, hard across the face. He held his breath.

She said, “If you open your mouth once more, I’ll slap it clear into next Tuesday. Now hush yourself. I’m going to go find Larsen.”

“You are?”

“I am. You, on the other hand, are heading west, so help me God-if only to get you away from us, because you’re going to get us shot. Clinton, kindly help this fellow get on that horse and then the rest of us can get moving, too.”

Clinton nodded at her like a man who was accustomed to taking orders, then hesitated briefly, because he was not accustomed to taking orders from a woman. Then he realized that he didn’t have any better ideas, so he took Dennis by the arm, led him to the horse, and helped him aboard. The student did not look particularly confident in the absence of a saddle, but he’d make do.

“Don’t you let him fall!” Mercy commanded.

Clinton slapped both horses on the rear, and the beasts took off almost cheerfully, so delighted were they to be leaving the scene. The remaining members of the ragtag party had no time to discuss further strategy. No sooner had the horses disappeared between the trees, headed generally west, than the southern side of the fighting line met them at the road.

The soldiers rushed up with battle cries, leading carts with cannon, and crawling machines that carried antiaircraft guns modified to point lower, as necessary. The crawling machines moved like insects, squirting oil and hissing steam from their joints as they loped forward; and the cannon were no sooner stopped than braced, and pumped, and fired.

On the other side of the road, the northern line was likewise digging in. Soldiers were hollering, and in the light of a dozen simultaneous flashes of gunpowder and shot, Mercy saw a striped flag waving over the trees. She saw it in pieces, cut to rags by shadows and bullets, but flying, and coming closer. All around Mercy, soldiers cast up barricades of wood or wire, and where cannon felled trees, the trees were gathered up-by the men themselves, or with help from the crawling craft, which were equipped with retracting arms that could lift much more than a man.

Some of the soldiers stopped at the strange band of misfits beside the road, but not for long. A wild-eyed infantryman pointed at the ruins of the cart and hollered, “Barricade!”

In thirty seconds, it was hauled out of the road and then was further dissected for dispersing along the line.

Clinton was back in his element, among his fellow soldiers. He took Gordon Rand by the arm, since Gordon seemed the least injured and most stable male civilian present, and said, “Get everyone to the back of the line, and then take them west! I’ve got to get back to my company!”

Everyone was shouting over the ferocious clang of the war, now brought into the woods-which compressed everything, even the sound, even the smell of the sizzling gunpowder. It was like holding a battle inside someone’s living room.

Gordon Rand replied, “I can do that! Which way is west again?”

“That way!” Clinton demonstrated with his now-characteristic lack of precision. “Just get to the back of the line, and ask somebody there! Go! And run like hell! Their walker is getting closer; if ours don’t catch up, we’re all of us fish in a barrel!”

Most of the party took off running behind Rand, but Ernie hesitated. “Nurse?” he said to Mercy, who was looking back down the road, the way they had come.

“We’re still missing the captain, and the copilot, and Larsen.” She looked at Ernie. “I told Dennis I’d try and find him, and I mean to. Go on,” she urged. “I’ll be better off by myself. I can duck and cover, and I’ve got my red cross on.”

She mustered a smile that was not at all happy.

Ernie didn’t return it. He said, “No way, ma’am. I’m staying with you. I’m not leaving a lady alone on a battlefield.”

“You’re not a soldier.”

“Neither are you.”

It was clear that he wouldn’t be moved. Mercy sized that up in a snap; she knew the type-too chivalrous for his own good, and now he felt like he owed her, since she’d done what she could to take care of his hand. Now he was bound to take care of her, too, or else leave the debt to stand. Yes, she knew that kind. Her husband had been that kind, though she didn’t take the time to think about it right then.

“Suit yourself,” she told him. She lifted up her cloak, pulling the hood up over her head and adjusting her satchel so that the red mark stood out prominently. It wasn’t a shield, and it wasn’t magic, but it might keep her from being targeted. Or it might not.

“Behind the barrier-we can’t jump it, not now,” she said. It was amazing, how the thing had gone up while they stood there, piecemeal by rickety piecemeal, made up of logs and metal shards, and strips of things meant to tear human flesh beyond repair. Even if she could’ve fit through it, that would’ve left her in the middle of the worst of the cross fire, and that wouldn’t do. Especially not with Ernie tagging along.

So they wound their way through the soldiers, getting sworn at, shouted at, and shoved toward the safety they didn’t want every step of the way until they’d gone far enough east, away from the relative safety of the rails, that the barricade hadn’t yet found purchase and the road was not quite the highway of bullets that it had become farther up the way.

Mercy dashed into the road, crying out for Larsen-wondering if she’d passed him already in the turmoil, and wondering if he’d even survived falling out of the swiftly moving cart. “Captain? Mr. . . . Mr. Copilot? What was his name again? Scott something? Mr. Scott? Can anyone hear me?”

Probably more than a few people could hear her, but it sounded like the fighting was heating up back where the cart had crashed and been disassembled, and no one was paying any attention to the cloaked nurse and the bandaged dirigible crewman.

“Anyone?” she tried again, and Ernie took up the cry, to as much effect.

Together they tried to skirt the line of trees and keep their heads low as they walked up and down the strip where they concluded the cart had most likely come apart. And finally, off to the side and down a rolling culvert, into a cut in the earth where spring rain had carved a deep V into a hill, they got a response.

“Nurse?” The response was feeble but certain. It called like the men called from the cots, back at the hospital. Nuss?

They scarcely heard it over the battle, and it was all Mercy could do to concentrate on the sound-the one little syllable-over the clash a hundred yards away. The footsteps were still stomping, too, and stomping closer with every few steps; she shuddered to imagine what kind of machine this might be, that walked back and forth along the front and sounded much larger than any gun . . . maybe even larger than the Zephyr itself. Whatever it was, she didn’t want to see it. She only wanted to run, but there came that voice again, not quite crying, but pleading: “Nurse?”

“Over here!” Ernie said. “He’s down here!” And he was already sliding down there, toward the rut in the earth where Larsen had landed.

“I thought it was you,” Larsen said when Mercy reached him. “I thought it must be. Where’s Dennis, is he all right?”

“He’s fine. He’s on his way to the rail lines, where the train’ll pick him up and run him to Fort Chattanooga. We had to make him go, but he went. I told him I’d come looking for you.”

“That’s good.” He closed his eyes a moment, as if concentrating on some distant pain or noise. “I think I’m going to be just fine, too.”

“I think you might be,” she told him, helping him sit up. “Did you just crash here, or roll here? Is anything broken?”

“My foot hurts,” he said. “But it always hurts. My head does, too, but I reckon I’ll live.”

She said, “You’d better. Come on, let me get you up.”

“I remember there was a big snapping sound, and everything came apart. And I was flying. I remember flying, but I don’t recall anything else,” he elaborated while the Mercy and Ernie pulled him upright

and to his feet. His cane was long gone, but he waved away their attempts to assist him further. “I can do it. I’ll limp like a three-legged dog, but I can do it.”

“I don’t suppose you’ve seen the captain, or the copilot, have you?” asked Ernie.

“No, I haven’t. Like I said, I went flying. That’s all.”

“You’re a lucky son of a gun,” Mercy told him.

“I don’t feel real lucky. And what’s that noise?”

“It’s the line. It’s caught up to us. Come on, now. Other side of the road. Get down low, and make a dash for it-as much as you’re able. You landed on the Yankee side, so don’t go thanking your lucky stars quite yet.”

But soon they were ducking and shuffling, flinging themselves across the road and back to gray territory, and not a moment too soon. The barricade-makers were shouting orders back and forth at one another, extending the line, setting up the markers along the road. They ordered Mercy and the men to “Clear the area! Now!”

Larsen yelled back, “We’re civilians!”

“You’re going to be dead civilians if you don’t get away from this road!” Then the speaker stopped himself, getting a good look at Mercy. “Wait a minute. You a nurse?”

“That’s right.”

“You any good?”

“I’ve saved more men than I’ve killed, if that’s what you want to know.” She helped hoist Larsen down over the drop-off at the road’s edge, leaving herself closer to the dangerous front line. She stared down the asker, daring him to propose one more stupid question before she kicked him into Kansas.

“We got a colonel with a busted-up arm and chest. Our doctor took a bullet up the nose and now we’ve got nobody. The colonel’s a good leader, ma’am. Hell, he’s just a good man, and we’re losing him. Can you help?”

She took a deep breath and sighed it out. “I’ll give it a try. Ernie, you and Larsen-”

“We’ll make for the rails. I’ll help him walk. Good luck to you, ma’am.”

“And to the pair of you, too. You-” She indicated the Reb who’d asked her help. “-take me to this colonel of yours. Let me get a look at him.”

“My name’s Jensen,” he told her on the way between the trees. I hope you can help him. It’s worse for us if we lose him. You, uh . . . you one of ours?”

“One of yours? Sweetheart, I’ve spent the war working at the Robertson Hospital.”

“The Robertson?” Hope pinked his cheeks. Mercy could see the flush rise up, even under the trees, in the dark, with only a sliver of moonlight to tell about it. “That’s a damn fine joint, if you’ll pardon my language.”

“Damn fine indeed, and I don’t give a fistful of horseshit about your language.”

She looked back once to see if Larsen and Ernie were making good progress away from the fighting, but the woods wouldn’t let her see much, and soon the cannon smoke and barricades swallowed the rest of her view.

Jensen towed her through the lines, guiding her around wheeled artillery carts and the amazing crawling transporters. She gave them as wide a berth as she could, since he told her, “Don’t touch them! They’re hot as hell. They’ll take your skin off if you graze them.”

Past both good and poorly regimented lines of soldiers coming, going, and lining up alongside the road they dashed, always back-to the back of the line-following the same path as the wounded, who were either lumbering toward help or being hauled that way on tight cotton stretchers.

Back on the other side of the road, on the other side of the line, she heard a mechanical wail that blasted like a steam whistle for twenty full seconds. It shook the leaves at the top of the trees and gusted through the camp like a storm. Soldiers and officers froze, and shuddered; and then the wail was answered by a returning call from someplace farther away. The second scream was less preternatural, though it made Mercy’s throat cinch up tight.

“It’s only a train, out there,” she breathed.

Jensen heard her. He said, “No. Not only a train. That metal monster they got-it’s talking to the Dreadnought.”

“The metal monster? The . . . the walker? Is that what they called it?” she asked as they resumed their dodging through the chaos of the back line. “One of your fellows told me they have one, but I don’t know what that is.”

“Yeah, that’s it. It’s a machine shaped like a real big man, with a pair of men inside it. They armor the things up and make them as flexible as they can, and once you’re inside it, not even a direct artillery hit-at real close range-will bring you down. The Yanks have got only a couple of them, praise Jesus. They’re expensive to make and power.”

“You sound like a man who’s met one, once or twice.”

“Ma’am, I’m a man who’s helped build one.” He turned to her and flashed a beaming smile that, for just this once, wasn’t even half desperate. And as if it’d heard him, from somewhere behind the Confederate lines a different, equally loud and terrible mechanical scream split the night across the road with a promise and a threat like nothing else on earth.

“We got one, too?” she wheezed, for her breath was running out on her and she wasn’t sure how much longer she could keep up this pace.

“Yes ma’am. That-there is what we like to call the Hellbender.”

She saw its head first, looming over the trees like a low gray moon. It swiveled, looking this way and that, the tip of some astounding Goliath made of steel and powered by something that smelled like kerosene and blood, or vinegar. It strode slowly into a small clearing, parting the trees as if they were reeds in a pond, and stood up perfectly straight, before emitting a gurgling howl that answered the mechanized walker on the other side of the road-and sent out a challenge to the terrifying train engine, too.

Mercy froze, spellbound, at the thing’s feet.

It was approximately six or seven times her height-maybe thirty-five or forty feet tall, and as wide around as the cart that had carried her away from the Zephyr. Only very roughly shaped like a man, its head was something like an upturned bucket big enough to hold a horse, with glowing red eyes that cast a beam stronger than a lighthouse lamp. This beam swept the top of the trees. It was searching, hunting.

“Let’s go.” Jensen put himself between her and the mechanized walker, flashing it a giant thumbs-up before leading her toward a set of flapping canvas tents.

But she couldn’t look away.

She couldn’t help but stare at the human-style joints that creaked and bent and sprung, oozing oil or some other industrial lubricant in black trails from each elbow and knee. She had to watch as the gray-skinned thing saw what it was looking for, pointed itself at the road, and marched, spilling puffs of black clouds from its seams. The mechanized walker didn’t march quickly, yet it covered quite a lot of space with each step; and each step rang against the ground like a muffled bell with a clapper as large as a house. It crashed against the ground with its beveled oval feet and began a pace that could best be described as a slow run.

A cheer went up behind the Confederate line as the walker went blazing through it. Everyone got out of the way. Hats were thrown up and salutes were fired off.

Back in the woods, somewhere on the southern line, an explosion sent up a fireball so much bigger than the tree line that, even though it must’ve been a mile away, Mercy could see it, and imagine she felt the heat of it.

Jensen said, “You got here on that dirigible, the one that went down?”

“That’s right,” she told him. “And it just went up in flames, didn’t it?”

“Yup. Hydrogen’ll do that.”

“What about that thing? The Hellbender?”

“What about it?” he asked.

“What does it run on? Not hydrogen?”

He shook his head and then ducked under a tent flap, indicating that she should do likewise. “Hell no. Texas done developed it, so it runs on processed petroleum. Can’t you smell it?”

“I can smell something.”

“Diesel. That’s w

hat they call it, and that’s why our Hellbender’s gonna take down their . . . whatever they call theirs. Theirs just run on steam. They move all right, but they run so hot, they can’t keep pace with ours, not for very long. Not without cooking the men who ride inside ’em.” He paused his exposition to salute a uniformed fellow in the tent’s corner. Then he said, “Chase,” to acknowledge a second man who was sitting on a camp stool beside a cot. “Ma’am, this is George Chase-he’s been looking after the colonel. And there, that’s Colonel Thaddeus Durant. You can see he’s not doing so good.”

“I can see that,” she said, and went immediately to the colonel’s side. She dragged a second camp stool to the cot’s edge and tugged a lantern out of George Chase’s hand.

He gave clear consideration to mounting a protest, but Jensen shushed him by saying, “She’s a nurse from the Robertson joint, George. Dropped right out of the sky, she did. Give her some breathing room.”

George scooted his stool back and said, “I don’t know what to do. I fix machines; I don’t know how to fix things like this!”

She swung the lantern over the pulp of the colonel’s face, neck, shoulder, and ribs, and guessed that he’d taken a close proximal blast of grapeshot, or something messier. Peeling back the blanket they’d thrown across him, she followed the damage like it was a trail marked out on a map. The blanket stuck to him where the makeshift bandages had bled clean through. Everything was beginning to dry to a sticky, wet paste of cotton, wool, and shredded flesh.

“Gentlemen, I’m not entirely sure what to tell you-”

“Tell us you can save him!” George Chase begged.

She wouldn’t tell them that. Instead she said, “I need all the clean rags you can get your hands on, and your doctor’s medical bag if you can scare it up for me. Then I’m going to need a big pot of clean water, and if you find some that’s good and hot, so much the better.”

“Yes ma’am.” George saluted her out of habit or relief on his way out of the tent, thrilled to have been given a task.

Maplecroft

Maplecroft Chapelwood

Chapelwood Fathom

Fathom Hellbent

Hellbent Jacaranda

Jacaranda Four and Twenty Blackbirds

Four and Twenty Blackbirds Dreadnought

Dreadnought Dreadful Skin

Dreadful Skin Bloodshot

Bloodshot Tanglefoot

Tanglefoot Clementine

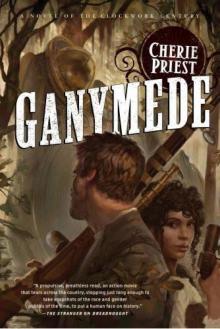

Clementine Ganymede

Ganymede The Inexplicables

The Inexplicables Not Flesh Nor Feathers

Not Flesh Nor Feathers Wings to the Kingdom

Wings to the Kingdom Fiddlehead

Fiddlehead Tanglefoot: A Story of the Clockwork Century

Tanglefoot: A Story of the Clockwork Century The Agony House

The Agony House Ganymede (Clockwork Century)

Ganymede (Clockwork Century) The Inexplicables (Clockwork Century)

The Inexplicables (Clockwork Century) Clementine tcc-2

Clementine tcc-2 Grants Pass

Grants Pass Dreadnought tcc-3

Dreadnought tcc-3 Ganymede tcc-4

Ganymede tcc-4